Writing Rails of War

I grew up on a farm in Indiana fascinated by a red photo album entitled “India.” It was an odd little book of black and white snapshots from a faraway place with dark-skinned natives and exotic animals. The photographs, mounted with sticker corners on black pages, had captions written in white ink. There were elephants and tigers and water buffalos and young American soldiers clowning for the camera in one shot and caught in serious endeavors in the next. There were jeeps set to rails, mammoth steam cranes, and locomotives galore. My father, James Hantzis, returned from India with the album and with stories about his service in Parbatipur, Province of Bengal, India.

I grew up on a farm in Indiana fascinated by a red photo album entitled “India.” It was an odd little book of black and white snapshots from a faraway place with dark-skinned natives and exotic animals. The photographs, mounted with sticker corners on black pages, had captions written in white ink. There were elephants and tigers and water buffalos and young American soldiers clowning for the camera in one shot and caught in serious endeavors in the next. There were jeeps set to rails, mammoth steam cranes, and locomotives galore. My father, James Hantzis, returned from India with the album and with stories about his service in Parbatipur, Province of Bengal, India.

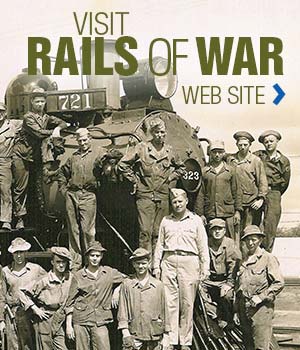

Dad was a GI railroader, a journeyman machinist. After passing the aviation cadet test with flying colors, he was drafted for his skills into a railroad battalion, the 721st. His unit was sponsored by the New York Central Railroad and was one of five operating battalions that took over the strategic line of communications from Calcutta to Ledo, India. The railroad and the Port of Calcutta were at the end of a 14,000-mile link to the industrious United States and formed the supply backbone for the Allies in the China-Burma-India theater (CBI). CBI would prove the worst land defeat for the Imperial Japanese Army of World War II.

Dad was a GI railroader, a journeyman machinist. After passing the aviation cadet test with flying colors, he was drafted for his skills into a railroad battalion, the 721st. His unit was sponsored by the New York Central Railroad and was one of five operating battalions that took over the strategic line of communications from Calcutta to Ledo, India. The railroad and the Port of Calcutta were at the end of a 14,000-mile link to the industrious United States and formed the supply backbone for the Allies in the China-Burma-India theater (CBI). CBI would prove the worst land defeat for the Imperial Japanese Army of World War II.

GIs had it rough but, as a kid, I didn’t see that in the photo album. I didn’t see the soaking monsoons, the 100-degree temperatures, the mold and mildew, the jungle rot, the disease, the deadly working conditions, the mud, and pests. I didn’t see the saboteurs. I didn’t see the Bengal Famine that killed millions and engulfed the entire northeast of India during their tour. It wasn’t until I began researching the book in 1993 that I started to grasp the difficulties dad and his unit faced.

In September 1999, my wife Kathy and I attended a reunion of the 721st Railway Operating Battalion in upstate New York. There we met nineteen of the men who served. Most were railroad retirees. They had returned from the war, continued their railroad employment and finished their working lives as railroaders. From these men I received original source materials, enlisted men’s histories, official battalion histories, shipboard newsletters, artifacts, photos, and stories. The men were welcoming and encouraging, and I believe they accepted me not simply because my father was in their unit but also because I was a railroader. I had worked in the operating crafts as a freight brakeman-conductor for twelve years. Most railroaders are reluctant to tell non-railroaders the most tangled railroad stories because non-railroaders usually find them hard to believe. And, credibility is important to railroaders.

In September 1999, my wife Kathy and I attended a reunion of the 721st Railway Operating Battalion in upstate New York. There we met nineteen of the men who served. Most were railroad retirees. They had returned from the war, continued their railroad employment and finished their working lives as railroaders. From these men I received original source materials, enlisted men’s histories, official battalion histories, shipboard newsletters, artifacts, photos, and stories. The men were welcoming and encouraging, and I believe they accepted me not simply because my father was in their unit but also because I was a railroader. I had worked in the operating crafts as a freight brakeman-conductor for twelve years. Most railroaders are reluctant to tell non-railroaders the most tangled railroad stories because non-railroaders usually find them hard to believe. And, credibility is important to railroaders.

I began writing in earnest in 2000. By 2005, the sixtieth anniversary of the end of the war, I sent the men an author’s draft. I also sent the draft to family members, and, in my mind, I had accomplished my first goal, to get the story written and give it to the people who mattered. Since I was still working as a Grand Lodge Representative for the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAMAW), I had plenty on my plate besides writing.

Then, in 2010, on a trip to Indianapolis, sitting on the patio with my sister, Mary Ann, she casually asked if I remembered the box of letters that mom and dad had saved. I said no, and she went to the basement and retrieved 680 letters, in their original envelopes, dating from March 1941 to August 1945. I was pleased that they had survived but baffled by what to do with them.

Then, in 2010, on a trip to Indianapolis, sitting on the patio with my sister, Mary Ann, she casually asked if I remembered the box of letters that mom and dad had saved. I said no, and she went to the basement and retrieved 680 letters, in their original envelopes, dating from March 1941 to August 1945. I was pleased that they had survived but baffled by what to do with them.

I retired from the IAMAW in January 2013 and began working my way through the family letters. First, I scanned all the letters into PDFs then read and noted them. Then, I exported my notes into a 122-page Word document and began weaving the new color and details back into my original storyline. When I finished, I had a two-volume author’s draft that was a thousand pages long.

Enter literary agent, Ronald Goldfarb, and the world of commercial publishing.

I called Ron at the suggestion of my primary care physician, Gilbert Eisner, M.D., a well-connected and caring person. Ron agreed to review the manuscript and afterward suggested an edit to create a “war story.” Previously, the author’s draft could have been called “All Things Hantzis,” or, as my friend Josh suggested, “Things that Steve Knows. ”Ron introduced me to Jefferson Morley, an accomplished author, and we worked together for six months to create the product submitted for publication. The manuscript went out to potential publishers in May 2015, and in September the University of Nebraska Press said they would publish the book.

I called Ron at the suggestion of my primary care physician, Gilbert Eisner, M.D., a well-connected and caring person. Ron agreed to review the manuscript and afterward suggested an edit to create a “war story.” Previously, the author’s draft could have been called “All Things Hantzis,” or, as my friend Josh suggested, “Things that Steve Knows. ”Ron introduced me to Jefferson Morley, an accomplished author, and we worked together for six months to create the product submitted for publication. The manuscript went out to potential publishers in May 2015, and in September the University of Nebraska Press said they would publish the book.

Commercial publishing was, and is, new to me. But, everyone at University of Nebraska Press has been helpful and patient. It’s been a pleasure to work with them, and I’m lucky, indeed. Most importantly, the story of the 721st Railway Operating Battalion and the war in CBI, what historians often call “the forgotten theater,” is forgotten no longer. I hope you enjoy the book.

Steven James Hantzis