Over 59,000 women served in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps during World War II. Thousands more, like Mary Louise Hantzis, R.N., my mother, cared for war-wounded in the States. Mary worked with a noted orthopedic surgeon in Indianapolis and saw war-torn bodies on every round. For Veterans Day 2021, I offer this vignette, an origin story of her profession.

December 1853—French Battleship Charlemagne—Constantinople Harbor, Turkey

Northwestern squalls bore the sulfuric tail of tanneries and south-westerlies reeked of abattoir coppery effluence. The weather blew in circles and from every direction, it stank of dead meat. Pelting rain was all that kept Pierre-Yves from nauseating embarrassment. The icy sting braced him, standing watch on the bridge deck. Morning skies were as gray as the waves and if the sun had risen, Pierre-Yves was not a witness. Thankfully, two charcoal caustic plumes from the ship’s stacks fell astern in her ten-knot advance. Charlemagne’s 368 feet of laden armored decking rocked and wallowed on a sea sent from the devil below. Pierre-Yves fought the list and heave to maintain his watch on the Russian shore batteries.

Pierre-Yves wasn’t the only one who thought this deployment stupid. He wished he were home on his family’s farm near Artignosc sur Verdon tending to honeybees and olive trees. “Ah,” he thought, “It is the time of year for hunting the boars. This miserable trip was the work of fools. Ten minefields we have already sailed. Heaven is the weather in the south of France compared with the god-forsaken Bosporus.

“Parle à mon cul, ma tête est malade!” he grunted under his breath in frustration. [Stop bothering me!]

Other junior officers thought as he did, all faithful Catholics with the French prerogative of skepticism. A skepticism alive and well on this dubious expedition.

Pierre-Yves was a bright, lucky boy from a privileged family. He worked hard at the Université de Paris-Sorbonne to earn his degree in Nautical Engineering. As a patriotic Frenchman, he enlisted in the service of his country upon graduation and held the rank of lieutenant in the French Navy.

He spent late nights at the Sorbonne discussing philosophy, art, women, and religion. He was Catholic by birth and faith. But he could not fathom how a trivial matter, squabbling monks, justified sending an armada and thousands of men across the Mediterranean into hostile waters.

“All for what?” he asked himself. “To stymie Russians for a Greek misdemeanor supported by the Tsar? C’est plus qu’un crime, c’est une faute!” [It is worse than a crime, it is a blunder!]

“Over what?” he asked in silent monologue. “The keys to a church and a silver star?”

He visualized a pair of Greek Orthodox monks in tall hats and long gray beards slinking into the Church of the Nativity in the middle of the night. He smirked. He shook his head and rain flung from the double bills of his Napoleon hat.

In his visualization, now in full career, two fat buffoons kneeled on the marble, prying the fourteen-point silver star embedded in the ancient iron-stained grotto. He saw the Latin inscription, which he knew by heart, Hic de Virgine Maria Jesus Christus natus est. [Here Jesus Christ was born to the Virgin Mary.]

He imagined the simpletons secreting the prize under their robes and scurrying back to their monastery like burglars, common thieves. The monks’ motivations were mysterious. Rescue of the sacred symbol from the Catholics? Whatever they were thinking, whatever their crime, it wasn’t worth killing for, or being killed for.

“Hell, let the Greeks run the grotto. It doesn’t change the faith of those who believe and worship,” he muttered in exasperation.

“À cause de rien,” he thought. [For no reason.] “Now, France must sail to the rescue and restore the luminary for the honor of church and country? This is folly. Men should never put religion above reason. Not in affairs of state. When both religions pray to the same God? Orthodox or Catholic, what’s the difference? The direction in which they sign the cross?”

He raised the dripping brass telescope to his eye and scanned the Russian batteries. As he focused, a Latin phrase came to him from his late-night critiques at the Sorbonne, “Credo quia absurdum est.” [I believe it because it is absurd.]

Pierre-Yves was right. The Crimean War was absurd and deadly. Thieving monks were not the casus belli, although politicians presented it that way. The war arose from commerce and geography, with religion sprinkled atop for mass consumption.

The big players were France, Britain, and Turkey against Russia. From late 1853 to early 1856, half a million men fought and died and twice as many civilians starved or died from disease. Conscripted soldiers abandoned family farms and industrial centers in Europe. On the continent, food grew scarce and famine’s fellow travelers, typhus, and malnutrition reaped thousands. At the front, France, Britain, and Turkey lost 70,000 killed in battle and 183,000 to disease. Russia lost 256,000 evenly split between battle and disease. But the dialectic that Pierre-Yves studied so intently at the Sorbonne held. Amid misery, carnage, and senseless bloodletting arose beauty, art, and human betterment.

Because of the war, the United States purchased Alaska from Russia for a song. Russia, unhappy with the inferior quality of Alaskan furs, needed to keep the U.S. from entering the war on the side of her enemies. She offered our forty-ninth state for $7.2 million.

And, in early November 1854, a lithe, thirty-four-year-old woman with a kind, determined face arrived at the British Barrack Hospital in Scutari, Turkey, today’s Üsküdar. There on the Asian shore of the Bosporus, she gazed at the Blue Mosque, St. Sophia, and Topkapi Palace in clear view from the peninsula of Stamboul. Opulence played hard against the grisly toil of endless caregiving, horror, and desperate improvisation.

With her traveled thirty-eight women recruited from the safe confines of Western Europe. She trained them in sanitation and statistics and how to care for the injured and sick. She established her triage haven with little support from the military and active resistance from male doctors and orderlies. Then, at the battle of Inkerman, the women’s angelic custody of casualties transformed the medical profession. At night, amid moans and the stench of bloody bandaging, Florence Nightingale walked the aisles of cots at Scutari. She held a lamp aloft to guide her way and reassure the wounded.

Florence Nightingale invented and invested modern professional nursing. I, for one, am grateful. For had she not, my mother would have had to find other work, the same for my Aunt Pearl, Aunt Dorothy, and my niece, Kara.

A Lady with a lamp shall stand.

In the great history of the land,

A noble type of good,

Heroic Womanhood.

‘Santa Filomena’ by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1857

‑SJH

Memorial Day honors the sacrifice of veterans and all who served. But to a subset, Hoosiers, it’s also about the biggest sporting event on the planet. I count among them. Growing up in central Indiana, the Indianapolis 500 Mile Race was the soundtrack of our holiday weekend. My father, a China-Burma-India veteran, had the rare day off from being a machinist for General Motors. Dad relaxed with iced tea, watermelon, and my mother’s fried chicken once he finished whatever needed doing around our forty-acre farm. All the while, the radio broadcast the race and the versed, trustworthy voice of Tom Carnegie loosed the imagination.

Service in the nation’s defense and betterment might be a COVID-expanded view this Memorial Day. Allowed that latitude, I will blend two themes. My daughter’s service as a teacher at Park Hill High School in Kansas City, Missouri. And the 500 Mile Race.

Sara, like all American teachers, took on a perilous, stressful, and often thankless task this past year. And if you doubt that, read something else. With fingers crossed, it looks like Sara and her students will see better days ahead with the coming school year. Fingers crossed. For Memorial Day additional honors in 2021, I nominate Sara’s service and all teachers. Teachers, first responders, health care providers, those who care for the aged, grocery workers, delivery drivers, warehouse workers, meat packers, and farmworkers, all. Let them ride alongside veterans in this weekend’s fanciful parade.

I tried hard to make Sara a motorhead. And it worked. So, I know she’ll be listening to the soundtrack of Memorial Day weekend as she relaxes into a recuperative summer. Then, come fall, she will rejoin the front lines and battle again in America’s indispensable engagement. Here’s to you Sara, and all those who led America through the darkness.

It is early in the Pacific War, 1943. The Marines have taken Guadalcanal and the Americans now have an airbase to use against the Japanese. On this night and the following day, that advantage bedeviled America’s public enemy number one.

To accomplish the impossible, everybody played their part, mechanics, pilots, commanders, and intelligence officers. Working as a team, they put America precisely where it wanted to be at the precise moment to succeed. Everyone working together.

Let us remember our veterans. They, better than most, understand the value of unity.

18 April 1943 0145 hours—Henderson Airfield, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands

Sparks from the welding torch peppered the long-cuffed glove of Marvin’s right hand. Its stiff and tattered leather covered greasy fingernails, a callous palm, and raw, bloody knuckles. The black glass on his gray hood revealed none of the intensity in the eyes reflecting only the fireworks showering from the underside of the P-38 Lightning’s wing.

Master Sergeant Devers was accustomed to rush jobs. Last-minute modifications, seat-of-your-pants reckoning, and shade tree engineering were all par for the course. He proudly called his finished creations Kentucky Custom, even though he hailed from Ladoga, Indiana. The ground crews stationed on Henderson Airfield, codenamed Cactus, and home of the 339th Fighter Squadron, could improvise with the best. But tonight’s project was a mother.

The big drop tanks had arrived late the previous afternoon, flown in by four B-24 Liberators from the 90th Bomb Group at Port Moresby, New Guinea.[1] Now Marvin and his men had the job of fitting 310-gallon external fuel pods to eighteen aircraft designed for 165-gallon tanks. They had to do it quickly. The squadron had to be in the air, in formation, and leave Henderson, at exactly 0715 hours.

“We’re lucky,” thought Marvin. “Washin’ Machine Charlie must have a date. I hope she keeps him busy all night.” The thrashing sound of the Japanese aircraft’s unsynchronized propellers was the unwelcome prelude to bombs falling and nearby explosions. It was a distraction that no one needed that night.

Marvin stepped out from under the wing and away from the intense floodlights. He moved to the front of the central nacelle, flipped up his welder’s hood and lit a cigarette. He leaned on Miss Virginia’s nosecone under the barrels of her four 50-calibre Browning machine guns and right above her 20mm Hispano AN-M2C cannon. In the light rain he scanned the rutted, packed-coral airfield and half a dozen other work bays.[2]

Sparks were flying, floodlights were blazing and men in dirty coveralls moved purposely under giant tarpaulins in the revetments. Through the patter of the rain and the hiss of welding torches he heard strains of Glen Miller’s Serenade in Blue lilting from a pilot’s tent.

He thought to himself, “Whatever this mission is, it’s a big one. The brass has been on the move for the better part of three days.”

Then he thought, “Break’s over. I better get busy installing that big-ass ship’s compass in the Major’s cockpit.”

Marvin had often heard the pilots complain about the fluxgate and magnetic compasses in the P-38s. The pilots told him that the only time they knew their exact direction was when they were lining up for takeoff. Only then could the instruments be swung into proper alignment.

Marvin thought, “Wherever these guys are headed, it must be hard to find. Mitchell doesn’t want to take any chances, either way… Mitchell’s the CO and the Old Man gets what he wants.”

Marvin was curious about where the squadron was headed. He’d heard the rumors about the mission and thought, “That son-of-a-bitch must be out there thinking he’s out of range. That would be the only reason for the big drop tanks.”

He poured a cup of coffee from a dented metal thermos, took a sip, grimaced, and tossed the rest to the ground. He did a little math in his head. “The normal fuel consumption of the twin Allison V-1710, supercharged, liquid-cooled engines at 2,300 RPM maximum cruise power is 113 gallons per hour. Two gallons a minute.[3]

“The Lightning has a 410-gallon internal fuel capacity, and his crews were outfitting each of the birds with a 310-gallon drop tank and a 165-gallon tank. The squadron would leave base with 885 gallons onboard. He divided 885 by 120 and estimated that the birds could be in the air for seven hours, if they didn’t see combat.”

A Lightning in combat sucked gasoline like a tornado so he cut his estimate in half.

The Lightning had a top speed of a little better than 400 miles per hour, but usually cruised around 260. “So,” thought Marvin, “If the birds could be aloft for four hours it meant they could cover roughly 1,000 miles.”

He assumed they’d return to Henderson. Marvin couldn’t think of another friendly airfield in the God-forsaken Pacific. He thought, “Whoever or whatever they are targeting could be 500 miles away. Wherever they are headed, it is deep into Japanese territory… on Palm Sunday.”

The rest of the night went by quickly. A little before 0700 hours, Marvin swung Mitchell’s compass for the third time. Then he climbed down from the cockpit to join the rest of his ground crewmen who were watching the P-38s make ready for takeoff. Blue smoke belched from exhaust ports as all thirty-six engines snarled to life.

“So far so good,” thought Marvin.

The din of eighteen planes ready for launch perked up his weary mind and body. The acoustic signature of a P-38 was unmistakable. The twin V-12s of a solo P-38 made a quiet whuffle sound because superchargers muffled their exhausts. But all the planes idling together created a sonic pulse and a thunderous rhythm all their own. The sound sent a wave of power and pride coursing through the ground crews.

At 0710 hours, CO Mitchell revved Miss Virginia’s powerful V-12s to full RPMs and planted his feet on the aircraft’s brakes. He checked the ship’s compass heading for the last time to make sure it lined up with the runway, released his brakes and was airborne seconds later. Once in the air he circled Henderson at 2,000 feet awaiting the others.

Seventeen planes made it into the air. One busted a tire when the over laden bird struck a jagged piece of metal planking as it trundled down the runway. A few minutes after the formation departed, another had to turn back to Henderson because of a drop tank, fuel-feed malfunction. By then, Marvin was in the mess tent having his breakfast of Spam, dried eggs, and more coffee.

Major John W. Mitchell now had sixteen birds to complete Operation Vengeance. He was told it was a mission to which, “The President attaches extreme importance.” His plan of attack had to be adjusted.

The two missing planes were shooters from the four-plane Killer Section of the squadron. Maintaining absolute radio silence, CO Mitchell hand-signaled for Lieutenants Hine and Holmes to move up in formation and join Captain Lanphier and Lieutenant Barber as attackers. That left twelve fighters for the Cover Section.

Mitchell had set up other visual signals to command the squadron in flight. When he wanted the formation to tighten, he wagged his wings and when he want them to spread out, he kicked his rudders to make Miss Virginia fishtail.[4]

By 0725 hours, the squadron was in the air and Mitchell led them on a slow descent to the water. They flew just above the waves on a northwesterly course that kept them at least fifty miles away from the Japanese-held islands of New Georgia, Vella Lavella, and the Treasuries. Mitchell watched helplessly as a P-38 less than one hundred feet in front dipped into the froth of a wave tip and splattered saltwater on Mitchell’s windshield. With the smooth green ocean just thirty feet below and the blue sky as a horizon, depth perception was dreadful. But skimming the waves was the only way to avoid Japanese radar and lookouts.

The P-38 Lightning was designed for high altitude service where the air is cold. The plane had no cooler for the cockpit, and the sun beat down on the pilots in their low-flying greenhouses. Every pilot knew that you couldn’t open the canopy of a P-38 in flight without generating severe buffeting. And buffeting was the last thing anybody wanted flying thirty feet above the ocean. Especially since not every pilot had an inflatable rubber dinghy onboard. These survival rafts were in short supply, so the pilots cut cards to see who would carry one. The theory went that if a man ditched without a raft, someone with a raft would circle and throw his dinghy from the cockpit.[5]

The men sweated, counted sharks, manta rays or driftwood and some, including Mitchell, grew dangerously drowsy. The CO had been up most of the night studying maps and plotting navigation. He had managed a couple hours shut eye and was back up at 0430 hours rechecking his calculations.

By 0800 hours, Mitchell’s squadron was 285 miles from the planned interception. Precisely fifteen minutes earlier, exactly on time just as their commander insisted, two Japanese G4M Mitsubishi Betty bombers, took to the air from Lakunai Field, Rabaul. They were escorted by six Zero fighters. Flying conditions were perfect, and all expected a precise 0945 hours touchdown at Buin on Ballale Island, 315 miles away, just as Magic said they would.

Magic was the codename for the American cryptography team tasked with breaking the Japanese JN25 code. An American radio post in the Aleutians had intercepted a high-level Japanese transmission four days earlier, and its decryption started the chain of events that launched the 339th Fighter Squadron.

Mitchell’s job was to find and surprise the Japanese formation. He had planned well and carefully thought through the navigation and attack. But the odds seemed long indeed. He figured their chance for success was one in a thousand.

Twenty minutes after the Japanese left Rabaul, Mitchell changed course for the first time. He carefully watched his airspeed, compass and time and swung the squadron slightly to the north. They were abreast of Vella Lavella a half hour later when they made their second planned course change shifting ever more slightly again to the north. Mitchell made their final planned correction at 0900 hours and headed northeast toward the coast of Bougainville, forty miles away. He directed the squadron to begin a slow climb and test fire their guns.

Minutes later, Old Eagle Eyes, Lieutenant Canning, broke radio silence with a cool, “Bogeys! Eleven o’clock high.” Against the eight-thousand-foot-high Crown Prince Mountain Range on the southern coast of Bougainville specks in the sky became a formation.

Mitchell couldn’t believe his eyes, but there they were. The Betties were in the lead at about 4,500 feet. The Zeros formed a V in two sections of three 1,500 feet above the bombers and slightly to the rear. Every plane was brightly painted and looked brand new. They were right on schedule, 0935 hours, exactly where Magic said they would be.

The P-38s jettisoned their drop tanks and Mitchell’s section hauled back on their yokes and slammed their throttles to the firewalls as they climbed for altitude to cover the attackers. The four killers went straight at the two Betty bombers, but Lieutenant Holmes could not drop his tanks. He tried to jar them free and peeled off down the coastline, violently juking his P-38, hoping to shake them loose. Lieutenant Hine, his wingman, followed for protection but could barely keep up with all of Holmes didos or trick maneuvers. That left Lanphier and Barber to close on the bombers.

The Betties were slightly above them at one or two o’clock. Lanphier and Barber angled for a right-turning, pursuit-curve attack. The Zeros spotted the two Lightnings while the Betties were still a mile ahead and two miles to the right. The Japanese fighters dropped their belly tanks and dove on the P-38s.

The lead Betty nosed down into a diving turn to escape. With the Zeros on them, Lanphier banked slightly left to meet them head on. He cut loose a burst of machine gun fire and blew the middle Zero from the air, scattering the other two. This freed Barber to go for the bombers.

Barber turned right and saw one Betty going hell bent for leather in a downward 360-degree spiraling turn headed for the jungle. Barber fired the P-38’s non-converging weapons across the top of the fuselage at the right engine. At the same time Barber slid over to get directly behind the target and his fire passed through the Betty’s tail. He saw pieces of the rudder separate from the plane.

Barber kept firing. His 20mm cannon shook the P-38 with its dull POM-POM-POM report. With the Betty just one hundred feet in front of him, it suddenly snapped to the left and slowed rapidly. Barber screamed by the doomed craft at 425 miles per hour and saw smoke pouring from the right engine.

In the next instant, three Zeros began firing on Barber’s tail. He shoved the yoke forward and headed for the coastline on the deck at minimum altitude, as fast as the P-38 could fly. And thankfully, that was faster than the Zeros.

Holmes had finally shaken the faulty drop tank and returned with Hine to chase the Japanese fighters off Barber’s tail. As Barber looked back to check for pursuers, he saw a column of black, oily smoke rise from the jungle.

Lanphier, after downing the Zero and scattering the formation, found himself at about 6,000 feet. Below, he spotted the wounded Betty flying across the jungle canopy and began firing a long, steady burst at right angles across its path. He felt he was too far away for a hit and was surprised to see the Betty’s right engine and right wing burst into flame.

Holmes spotted the second Betty diving towards the sea and gave pursuit with Hine on his wing. They were delivering heavy fire from behind when Barber joined the attack and sent the bomber cartwheeling into the sea. Barber closed so fast on the Betty that his yoke vibrated fiercely as he reached the compressibility limit of the aircraft. Had he dived faster; the tails would have come off. His momentum carried him through the exploding debris.

With the two Betties down, the mission was accomplished and the P-38’s broke off to return the 410 miles to Henderson as best they could. All made it back save for Lieutenant Hine, who was listed as missing in action.[6]

Lanphier’s Lightning came home with two 7.7mm rounds through his rudder. Barber’s fighter limped home with a busted intercooler, a dented gondola, paint damage everywhere, and one hundred and four bullet holes. When he heard the first plane land, Sergeant Devers poured coffee into his thermos from the mess tent percolator, and he and his ground crews went to work immediately.

Fleet Admiral William F. Bull Halsey was notified of the mission’s success when Henderson transmitted the code phrase “Pop goes the weasel.” The last sentence in that brief dispatch was a reference to Doolittle’s raid on Tokyo which had taken place one year earlier. It read, “April 18 seems to be our day.”

The Admiral signaled back, “Congratulations to you and Major Mitchell and his hunters. Sounds as though one of the ducks in their bag was a peacock.” The Admiral showed his gratitude by sending the squadron two cases of combat whiskey, a commodity previously impossible to come by through official channels.

Near Buin, Lieutenant Hamasuna’s Japanese road construction gang received radio orders to form a search party. They found the bomber’s wreckage in the jungle near Moila Point a mile from the Panguna-Buin Road late the following day. It was tail number 323, Yamamoto’s airplane.

The wings and propellers had survived, but the fuselage had broken just ahead of the Rising Sun insignia. The section forward from there to the cockpit was burned out. No one had survived the crash.

Admiral Yamamoto’s body was found outside the fuselage in a cabin seat with his safety harness fastened. His head was drooped forward as if in deep thought. He had been shot through the skull by a machine gun bullet. He wore white gloves, ribbons and medals, and his left hand grasped the hilt of his sword with his right resting lightly upon it. The Sword of the Emperor, ever swift. In his pockets were a diary and copies of poems.

Yamamoto’s body was brought back to Buin by Corvette. There it was autopsied and cremated on a mountain in a military ceremony.[7] His ashes were placed in a square white wooden box lined with papaya leaves. Two papaya trees were planted at the site of his cremation.[8] His ashes were returned to Japan where his death was announced a month later.

On June 5, Yamamoto’s ashes were placed in a small coffin over which was draped a white cloth. The coffin was carried through Tokyo on a black artillery caisson and the procession was led by a military band playing Chopin’s Funeral March.[9]

Three million mourners came to his state funeral in Tokyo. The coffin wound its way to Tama Cemetery where his urn was placed in a grave next to Yamamoto’s mentor, Admiral Tojo.

A second, private ceremony was held in Nagaoka, his hometown. There, half of his ashes were buried next to his adopted father on the grounds of a Zen temple. A stone marked the grave with the simple inscription: Killed in action in the South Pacific, April 1943.

The news came as a shock in Japan. Yamamoto was the most popular military leader, second only to the Emperor. He was only the second commoner to be granted a state funeral.

Yamamoto was the driving force behind the Japanese war effort. He was more an icon than a man. But instead of boosting the morale of his troops after their defeat at Midway and the loss of Guadalcanal, as was his intent, his trip demoralized millions.

Americans were elated. Yamamoto’s name was synonymous with the attack on Pearl Harbor and they saw his death as payback. The news of Yamamoto’s death was held by the American military until the Japanese made their announcement. The Americans did this hoping to conceal the fact that the Japanese code had been compromised.

The Americans played their hand well. Even considering the surprise attack and the deadly efficiency of the American squadron, the Japanese refused to believe that anyone could break their code. They continued to pay the price of hubris.

In Yamamoto’s safe aboard the warship Musahi, navy officers found an epic poem in the Admiral’s hand. In Japanese, the form precisely alternated five and seven syllables per line. Linguists have paraphrased it thus:

Since the war began, tens of thousands of officers and men of matchless loyalty and courage have done battle at the risk of their lives, and have died to become guardian gods of our land.

Ah, how can I ever enter the imperial presence again? With what words can I possibly report to the parents and brothers of my dead comrades?

The body is frail, yet with a firm mind with unshakable resolve I will drive deep into the enemy’s positions and let him see the blood of a Japanese man.

Wait but a while, young men! – one last battle, fought gallantly to the death, and I will be joining you.[10]

– SJH Copyright © 2020 Steven James Hantzis

Endnotes

[1] Shelby L. Stanton. World War II Order of Battle (New York, NY: Galahad Books, 1984, p. 39).

[2] “Lockheed P-38 Lightning – USA” The Aviation History Online Museum Retrieved June 15, 2007 Online: http://www.aviation-history.com/lockheed/p38.html.

[3] “The Jeff Ethell P-38 Crash” AVweb Retrieved June 15, 2007 Online: http://www.avweb.com/news/safety/183014-1.html.

[4] Shelby L. Stanton. World War II Order of Battle (New York, NY: Galahad Books, 1984, p. 57).

[5] Shelby L. Stanton. World War II Order of Battle (New York, NY: Galahad Books, 1984, p. 28).

[6] “Rex Barber – Hero of the Yamamoto Mission – Heads West” 18th Fighter Wing Association Retrieved June 15, 2007 Online: http://www.18thfwa.org/statusReports/srpt25/page1.html.

The account of this highly disputed dogfight was largely taken from a source that supports Barber’s claim to have shot down Yamamoto. (18th Fighter Wing Association, Status Report No. 25, October 2001.) Lanphier also claims to have downed the Admiral’s airplane. The U.S. Army awarded a split-killer to each of the fighter pilots. The after-mission debriefing was delayed and horribly executed. The facts were never well-spelled out. In 1997, the American Fighter Aces Association gave Barber 100 percent credit for the shoot down of the bomber carrying Yamamoto. In 1998, the Confederate Air Force recognized that Barber alone and unassisted brought down Yamamoto’s aircraft and inducted him into the American Combat Airman Hall of Fame.

For further background see:

Rebecca Grant. “Magic and Lightening” Air Force Magazine March 2006 Retrieved June 15, 2007 Online: www.syma.org.

[7] Shelby L. Stanton. World War II Order of Battle (New York, NY: Galahad Books, 1984, p. 106).

[8] Shelby L. Stanton. World War II Order of Battle (New York, NY: Galahad Books, 1984, p. 106).

[9] Shelby L. Stanton. World War II Order of Battle (New York, NY: Galahad Books, 1984, p. 110).

[10] Shelby L. Stanton. World War II Order of Battle (New York, NY: Galahad Books, 1984, p. 109).

From Where They Came

This Memorial Day allow me to introduce a few of the men who led by example and molded America’s modern Special Operations Force. They were British, part of a secret organization called the Special Operations Executive (SOE). During World War II, SOE commandos fought in every theater and found time to come to America and train groups within the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the CIA. OSS commando units were called Operational Groups or OGs. The men in OGs were highly vetted, physically honed, and fluent in at least one foreign language. They weren’t spies; they fought behind enemy lines in American uniforms. Typically recruited from the U.S. Army and Marines, they were Norwegians, French, Italians, Austrians, Germans, Dutch, Hungarians, Spaniards, Poles, Czechs-Slovaks, Yugoslavs, Chinese, Korean, and Thai. And they were Greeks.

The manuscript I’m working on is American Andarte. Andarte is Greek for resistance fighter or guerilla. Greece was full of them during the Italian, Bulgarian, and German occupation of World War II. Most andartes belonged to either EDES or EAM-ELAS, rival resistance organizations within Greece. EAM-ELAS was larger and incorporated Greek communists, other progressives, and anti-monarchists. EDES was conservative and supported the king and accommodated the Germans. Believe me, Greek politics during World War II was complex. The book will supply details.

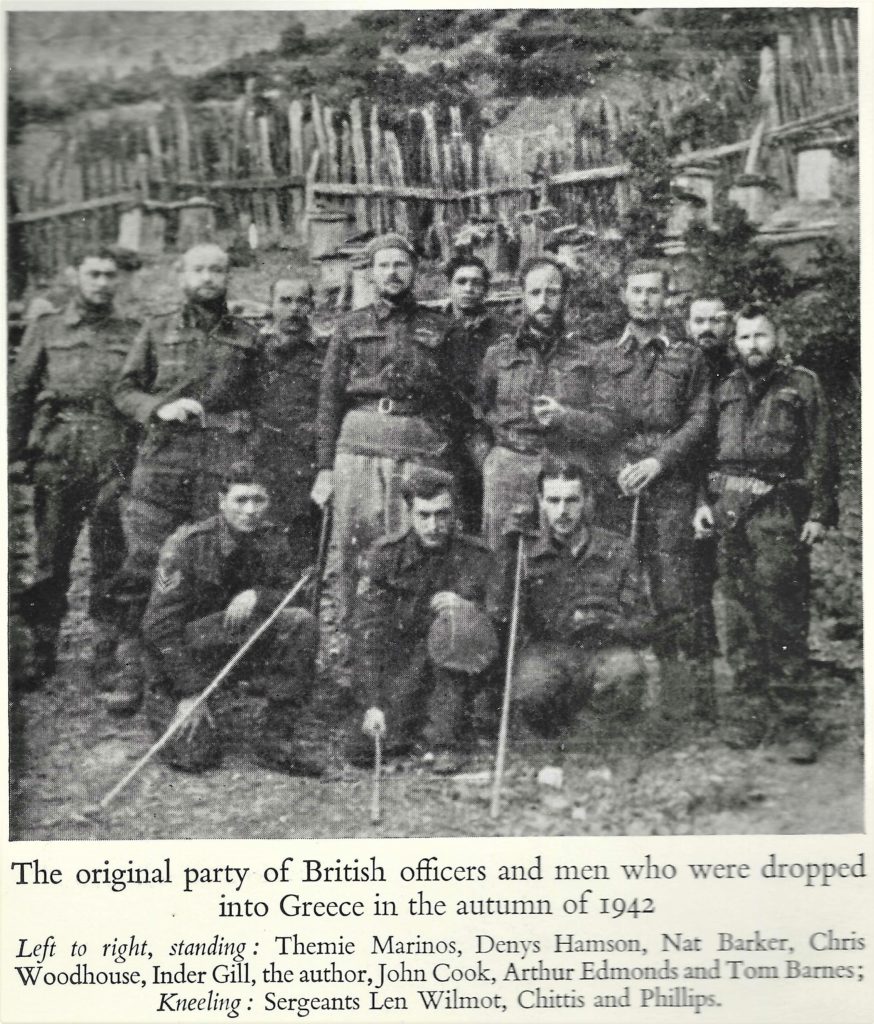

This vignette picks up in September 1942 with the first British SOE mission to Greece. The American OSS OGs would arrive a year and a half later in April 1944. Theirs is a fascinating story, classified until 1987. Until then, the CIA prohibited these American combat veterans from talking about their service. One hundred and eighty-one American OSS commandos served in Greece.

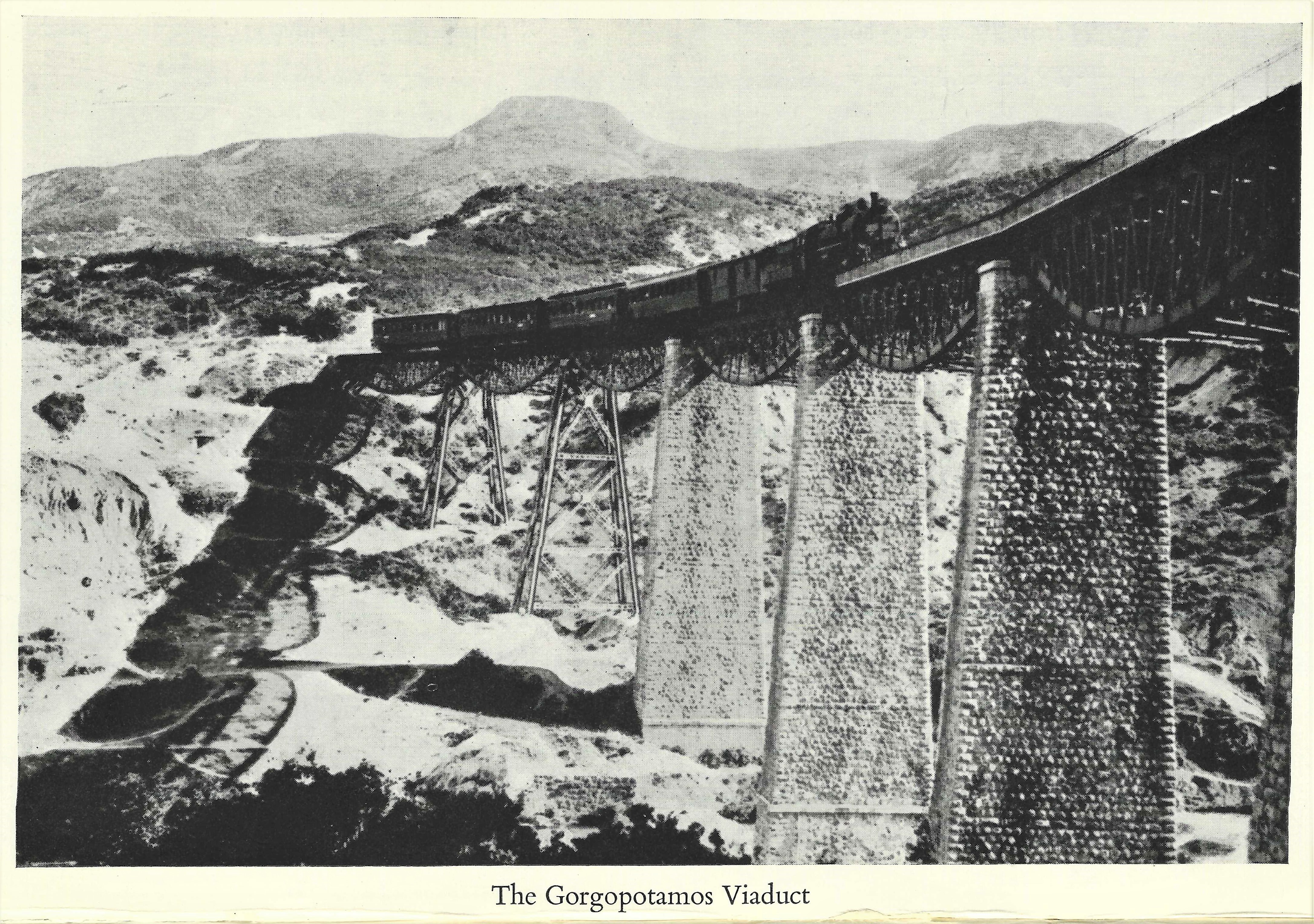

This is a section from a chapter in my manuscript so context might be foggy. The focus is on the British SOE and their first contact in Greece. The viaduct in this vignette is the Gorgopotamos Railroad Bridge. The sabotage of this crucial transportation link with the help of Greek andartes was their first SOE action. (There’s a great video about the mission featuring Monty Woodhouse.)

A few months later, the SOE struck again, this time alone. They brought down the highest railroad bridge in the country, the Asopos Viaduct, in an action believed impossible. Asopos is an entirely unique story covered in the manuscript and not for this post. It is enough to say that when the spans of Asopos Viaduct fell into the rushing river 330 feet below; the SOE made their mark on the history of warfare. The United States Army Special Operations Command today says that the attack on the Asopos Viaduct “was probably the single most spectacular exploit of its kind in World War II.” The Germans were so certain that the destruction of the Asopos Viaduct could only be an act of treachery that they shot the entire garrison guarding it that night.

Cairo, Egypt—September 1942

For all the complexity and drama that was Greek resistance politics, the Greek railway network was easy to understand. There was one standard-gauge mainline. It ran from the Port of Piraeus through Athens to Salonika in Greece, and from there to Sofia, Bulgaria, then Nis and Belgrade and Zagreb in Yugoslavia. At Zagreb, lines fanned out to Austria, Italy, and Hungary. The rail line carried forty-eight trains a day and completed an essential military line of communication. It stretched from the industrial centers of Germany through Piraeus to the Libyan ports of Tobruk and Benghazi. The Greek railroad was the only supply route with the ability to carry the weight of war. Over it rolled troops and supplies for occupation of the Balkans and the resupply of Rommel’s North Afrika Korps. It was a strategic target, of which the British took immediate notice. In the fall of 1942, they handed the problem to the Special Operations Executive (SOE), informally known as “The Baker Street Irregulars” or “Churchill’s Secret Army.”

On September 30, 1942, under a waning gibbous moon offering a bit too much light for the stealth intended, Lt. Colonel Eddie Myers, made a last check of men and supplies. Myers was a scrappy, assertive, thirty-six-year-old sapper from Kensington by way of the Middle East. The commander of the British SOE team climbed into an American-crewed B-24 Liberator on the tarmac of Deversoir Aerodrome. Deversoir was on the northern shore of Great Bitter Lake at the entrance of the Suez Canal.

Myers and three other SOE commandos boarded the first plane, and two more groups of four boarded two other planes. Each man, dressed in a British military uniform, carried an Enfield No. 2 Mk I .38 caliber revolver and a Fairbairn-Sykes commando dagger. They packed field dressings, and a Baker Street Kit comprising a compass that looked like a button, a map disguised as a silk scarf, a leather belt secreting two gold sovereigns, rations, torches, and poison pills for use if captured. They were parachuting into Greece. Their Sten submachine guns, grenades, and the detonators for their plastic explosives dropped separately in metal pod canisters.

They had done this before, two nights before. After flying four hours, eight hundred miles, over the Mediterranean into the mountains of Roumeli, Central Greece, they had turned away for Cairo. They had failed to spot the expected signal fires positioned to look like a cross. Tonight, was better. The pilot keyed the intercom and told Myers he thought he saw three fires burning in a valley below.

The snow on Mount Giona reflected the light of the moon and cast the palest glow on an alien world. The ancient name for Mount Giona is Aselinon Oros or moonless mountain. But tonight, the name misled. The Liberator descended to just above the peaks as Myers opened the bottom hatch in the airplane’s bay and jumped into the frigid darkness of the barely luminous unknown.

He fought updrafts from the mountain peaks. Buoyed and buffeted he blew away from his intended valley and drifted toward a forest of fir trees. He fought his heavy pack but couldn’t correct his descent. He landed high in a tall fir and crashed through its branches, ending on the ground with his parachute tangled above. His pack ripped from him in the fall, snagged on a stout limb and swung above. When he hit the ground, he sat for a few minutes in the snow and fir needles gathering his wits. The throbbing pulse of twelve, 14-cylinder Pratt & Whitney engines faded into the void. The Liberators were going home. It became silent, and Myers was alone.

There was no sign of the equipment pods or other commandos. Myers stood on the steep mountain slope, barely able to move without tumbling forward, and tried to stay calm. First, he lit a flare, and that drew no attention. Then he lit a bonfire which gave the same result. He stumbled towards the valley using trees as braking points for his descent. There in the valley, he met two Greek shepherds. Myers did not speak Greek, but the three pantomimed and worked out that they would stay put until dawn.

As the sun came up, Myers returned to the tree where he landed surprised that his parachute and pack were missing. That was when Tom Barnes, a New Zealander and one of Myer’s team, walked through the trees to Myers and the shepherds. He was unhurt. Barnes had received a signal from a third commando, Len Wilmot, and the two commandos went looking for him. The two shepherds went looking for the fourth commando, Denys Hamson, the only Greek-speaker in their group.

When the commandos and shepherds met at midday, the shepherds had found Hamson, and Wilmot appeared soon after. The team, one of three, was back together, intact, and Operation Harling was underway.

The second team, headed by Christopher Woodhouse, fared better. They landed seventeen kilometers north of Myers on the other side of Mount Giona. The four commandos landed without separation or injury. Soon Woodhouse’s team met, unexpectedly, armed men. The tension lifted when the andartes decided they were British and not German. The leader was a Greek who said he was expecting an explosive supply drop to blow up the retaining walls of the Corinth Canal. With him were two Cypriots, escaped prisoners of war.

The andartes led them to a village. There, Woodhouse, who went by Monty instead of Lord Terrington of Huddersfield, welcomed their equipment canisters retrieved by the villagers. But he watched in horror as children munched on the plastic explosive bars thinking they were fudge. They got sick but survived. Woodhouse, an Oxford-educated classics scholar and a fluent speaker of Greek, came first to understand the strangeness of occupied Greece, a country of scant resemblance to the land of Pericles.

Following the advice of a supportive villager the Woodhouse team moved to a cave on the eastern slopes of Mount Giona on a plateau called Prophet Elias. The cave was big enough to shelter all three commando groups. It was a three-day hike across a vast and rugged terrain. They trudged through deep snow in the valleys while the wind blew in gales cutting like the icy steel of a knife. Woodhouse welcomed Myers and his team and the two shepherds into their grotto sanctuary two days after arrival.

They knew the Italians were searching for them. The Italians had heard the Liberators on two nights. The SOE men moved to another cave that offered a better defense and tried to contact the third team.

The third team did not jump with the other two on September 30. They couldn’t spot signal fires and returned to Cairo. Three weeks later, they jumped blind and misjudged their location, dropping into the Karpenisi Valley near a large Italian garrison. Aris Velouchiotis commanded an EAM-ELAS unit that rescued the SOE team from certain capture. It took the three SOE teams a month to reunite.

Meanwhile, Woodhouse and Myers met the local EDES leader, Zervas, a short and rotund man of a carefree persona underlying his reputation as a brigand. Zervas controlled one hundred fighters. Later, they met Aris, the EAM-ELAS commander. He was thin, lanky, and hard-eyed, always alert and examining his surroundings. Aris commanded a larger, more disciplined force. His andartes controlled the territory on which rose the primary target of Operation Harling, the Gorgopotamos Bridge. But, before they could destroy one bridge, Myers had to build another.

To say EAM-ELAS and EDES were bitter rivals was to sugarcoat the reality. Both groups would not hesitate to attack and kill the other, given a provocation or a chance. Their politics clashed, and their leaders clashed. EAM-ELAS was the better organized and disciplined and larger. But British strategists fearing communist influence favored EDES. Myers and Woodhouse were to walk a diplomatic tightwire and forge a truce to carry out Operation Harling.

When they met with Aris of EAM-ELAS and Zervas of EDES, brandy helped to relax the grim Aris, and the carrot of arms and ammunition, and air support and resupply sweetened the proposition. Aris was less enthusiastic about the attack than Zervas. The EAM-ELAS top leadership believed that countryside military raids were less productive than urban actions. Aris was under orders “not to attack formed bodies of the enemy.”

Aris bucked EAM-ELAS leadership and agreed to take part. With the shaking of hands all around and toasts to the pact, EAM-ELAS and EDES pledged to work together for the attack on the Gorgopotamos Bridge. The British saw this arrangement as perhaps the start of a lasting reconciliation and a budding alliance between the organizations. But in Greece, the old is never far from the present.

Operation Animals set for June 21, 1943, called for an ambitious campaign of sabotage in Greece. SOE attacks with andarte support were to fool the Axis Powers into believing that Greece was the target of an Allied amphibious landing, instead of Sicily. Operation Animals was part of a broader campaign, Operation Barclay. This plan involved twelve fake Allied divisions, bogus troop movements, and corresponding fake radio communications. The deception was to fool the Germans into reinforcing Greece and forget about Sicily. Operation Mincemeat, the dead body, brought ashore in Spain, was part of Operation Barclay.

The British SOE commandos parachuted into Greece with three targets, bridges across the Papadia, Asopos, and Gorgopotamos rivers, all Roumeli railroad viaducts. Colonel Myers, while waiting to reunite with Woodhouse, reconnoitered all three and found Gorgopotamos Bridge the best choice.

Constructed in 1905 and considered an engineering marvel, the Gorgopotamos Bridge is ninety-five miles northwest of Athens. The bridge rises 112 feet to span the gorge and churning river for seven hundred feet. Gorgopotamos means the rushing river in Greek. Over it crossed a single line of railway, the lifeblood of Germany’s campaigns in the Balkans and North Africa.

As Myers crawled to his vantage at dawn, he could see through powerful binoculars the seven sub-linear spans supported by six pylons of the massive Gorgopotamos structure. The four central pylons were stone and would be impervious to the plastic explosives of the SOE. But iron piers, girders, and trusses supported either end. These would be the target for the four hundred pounds of shaped charges on the night of November 25, 1942.

One hundred Italians and five Germans guarded the bridge with pillboxes and heavy machineguns at either approach. With the SOE team of 12 and 86 fighters from EAM-ELAS and 52 from EDES, the attack would go forward with 150 fighters. The plan was simple, but the execution was treacherous.

Before 1100 hours, small groups of andartes went up the rail line both north and south to cut communications wires, halt advancing trains, and block any attempt at reinforcement. Then, at 1114 hours, all hell broke loose as the andartes attacked pillboxes at either end of the bridge. The southern position fell first with the Italians running to escape the attack. The northern defense fell when Myers sent his small contingent of reinforcements. As the attackers gained control of the bridge, the explosives team and eight mules made their way down the rough brush and slippery stones of the gorge. At the floor of the gorge, they waded into the powerful, unsettled currents of the river, and across a narrow plank bridge.

At the base of the bridge, the explosives team shaped and reshaped their charges and attached them to the girders. At 0130 hours on the morning of the 26th, the first explosion collapsed the two spans at either end of the bridge. The severed sections fell into the gorge with a crash to the cheers of fighters. An hour later, with explosives left over, the SOE sappers demolished the fallen spans where they landed. With the sky lightening at the hint of dawn, a green Very light spread an eerie glow on the gray-rose palate and signaled the retreat. The attackers withdrew at 0430 hours for a fifteen-hour trek to their hideout. The andartes suffered only four casualties and no killed-in-action. The SOE men were untouched and Myers estimated the Italian dead at thirty.

At the hideout, Myers expressed his gratitude to both Zervas and Aris. He told them the attack could not have been successful without them. Myers sent a messenger to Athens to arrange a supply drop of boots, clothing, arms, and whiskey for EDES and Zervas. Aris requested the same for EAM-ELAS, but Myers had no authority for the communist request. He instead gave Aris and EAM-ELAS 250 gold sovereigns. Myers told Zervas and Aris that he had recommended them for decorations and commended them for their service to the Allied cause. Zervas was grateful but Aris wanted none of it and told Myers he preferred boots for his fighters.

The German repair of the Gorgopotamos Bridge took six weeks, denying Rommel’s Afrika Korps two thousand trainloads of supplies. The repair to German respect for Italian courage under fire never happened. The Germans took over security for the entire railway system, straining their forces in Greece and the Balkans. Less than a month later, the 11th Luftwaffe Field Division moved into Attica north of Athens.

On December 1, 1942, ten villagers from tiny Ypati, hands bound, were marched to the rubble of the Gorgopotamos Bridge, and gunned down by the Germans. Four days later, the Germans killed another six hostages in the same way. It wasn’t the first blood retribution for the Germans in the administration of their doctrine of collective responsibility, and it wouldn’t be the last.

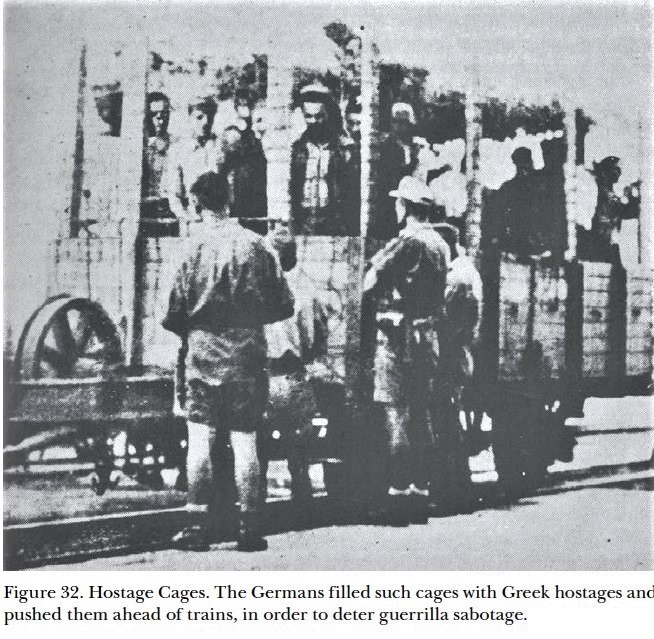

After Gorgopotamos, the Germans added klouves or crates to their trains. The Nazis filled these open railcars fenced with barbed wire with innocent Greek civilians, mostly women, and children. They coupled the cars ahead of the locomotives and shoved them first in line to discourage attack. It is impossible to overstate Nazi barbarity. Their crimes of taking hostages, and retaliatory killings, were sickening. At the Nuremberg Trials following the war, the Greek government reported 91,000 Greeks murdered as hostages and 800 villages and towns destroyed by the German occupation forces. – SJH Copyright © 2019 Steven James Hantzis

Notes

[1] http://oss-og.org/ [1] http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-WH2-2Epi-c2-WH2-2Epi-j.html page 24 [1] Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies, CASE STUDY IN GUERRILLA WAR: GREECE DURING WORLD WAR II, REVISED EDITION, United States Army Special Operations Command, page 58. [1] Myers, E.C.W. Greek Entanglement. Alan Sutton, 1985. https://books.google.com/books?id=NP1mAAAAMAAJ. Page 184. [1] Churchill’s Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare, The Mavericks Who Plotted Hitler’s Defeat – Giles Milton, page 206. [1] Churchill’s Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare, The Mavericks Who Plotted Hitler’s Defeat – Giles Milton [1] Myers, E.C.W. Greek Entanglement. Alan Sutton, 1985. https://books.google.com/books?id=NP1mAAAAMAAJ. Page 43 [1] Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies, CASE STUDY IN GUERRILLA WAR: GREECE DURING WORLD WAR II, REVISED EDITION, United States Army Special Operations Command, page 29 [1] Using Robotic Theodolites (RTS) in Structural Health Monitoring of Short-span Railway Bridges, P. Psimoulisa,b *, S. Stirosa, a Geodesy Lab., Dept. of Civil Eng., University of Patras, Patras, Greece – stiros@upatras.gr, b Geodesy and Geodynamics Lab., ETH Zurich, Schafmattstr. 34, Zurich, Switzerland – panospsimoulis@ethz.ch, page 1 https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/2011/2011_lsgi/session_1e/psimoulis_stiros.pdf [1] Myers, E.C.W. Greek Entanglement. Alan Sutton, 1985. https://books.google.com/books?id=NP1mAAAAMAAJ. Page 44 [1] Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies, CASE STUDY IN GUERRILLA WAR: GREECE DURING WORLD WAR II, REVISED EDITION, United States Army Special Operations Command, page 39 [1] Churchill’s Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare, The Mavericks Who Plotted Hitler’s Defeat – Giles Milton, page 218. [1] German Antiguerrilla Operations in the Balkans (1941-1944), CMH Publication 104-18 page 19. [1] Yada-Mc Neal, Stephan D.. Places of Shame – German and Bulgarian War Crimes in Greece 1941-1945. N.p.: Books on Demand, 2018. Page 137 [1] http://www.occupation-memories.org/en/deutsche-okkupation/Wichtige-Begriffe/index.html [1] http://www.occupation-memories.org/en/deutsche-okkupation/repressalien/index.html

You’ve finished training, you’re inoculated, and your paperwork is filed. Now, it’s time to board an overloaded, repurposed luxury liner and outlast the chaotic sea and a determined enemy. You know not your destination, that they will tell you along the way. Your only clue is that you are sailing west from California.

Fifteen million men and women of the United States armed forces faced similar circumstances during World War II. Not all were going to India like the 721st Railway Operating Battalion and the five thousand GI’s in their Military Railway Service (MRS), but all were bound for the unknown. On Veterans Day, 2019, I hope this vignette helps us appreciate those who served at a moment in their lives when all that came before resolved into what lies ahead.

This vignette precedes the narrative in Rails of War, the story of my father’s railway operating battalion in World War II. The book follows the men of the 721st on their journey to India, through their twenty-two months in-country, through fires and famine, monsoons, and crippling heat, as they move the weight of war on a foreign, outdated system. At war’s end, with their mission accomplished, their return trip takes them around-the-world. If you’d like to read more about the 721st and the China-Burma-India theater, the book is widely available.

9 December 1943, 1600 Hours – Camp Anza, California

A gaggle of GIs went to the orderly room to check the shipping list the evening before, and there they were. Amidst the anxious cluster of young men staring at the cork bulletin board, one anonymous soldier piped, “Well boys, I guess it’s time for a boat ride. Don’t forget your swimsuits and bathing caps.”

The 721st had finally received orders to ship out, but the rumor mill had been working overtime for two days before that. Word had reached them from the docks in Wilmington that their locomotives, rolling stock, section equipment, and machine tools had arrived. So, they knew it wouldn’t be long.

Besides getting their gear organized and stocking up on last-minute purchases, most men wrote home knowing that they would not be able to mail any more letters until they got to wherever the Army was sending them. By then, all mail home would be subject to enemy attack. They had been under a communications blackout since furloughs were canceled at Camp Atterbury after Thanksgiving – no letters, no telephone calls, and no telegrams.

They didn’t much regret leaving Camp Anza. The camp had beer, malted milk, and ice cream at the Post Exchange. It had a comfortable movie theater and an enormous mess hall with generous portions of good chow, and all the fresh fruit the men could eat. Still, it wasn’t a place where you spent much time or grew attached.

The camp was named for the intrepid Spanish explorer, Juan Bautista Anza. In the 1770s, Anza was the first European to establish an overland trail from Mexico to the Pacific coast of California through the continent’s hottest desert, the Sonoran. The Spanish had been looking for such a route for over two hundred years. Like Señor Anza, most GIs were simply passing through.

In 1942, the federal government bought 1,239 acres sixty miles east of Los Angeles from the heirs of Willits J. Hole, a wealthy businessman, landowner, entrepreneur, and successful yacht racer of the 1920s. Construction began in July 1942, and the base was finished in February 1943. The Camp was officially activated in December 1942 as Headquarters, Arlington Staging Area.

Stays at Camp Anza were brief. The 721st spent ten days there. But the total population of the base often ranged up to twenty thousand. It was a bustling beehive of activity through which more than 600,000 troops passed during the war.

Camp Anza was a staging area whose purpose was to prepare soldiers for overseas deployment. Base personnel immunized soldiers and helped them write their wills. APO mail numbers were assigned so that loved ones could stay in touch. Furlough pay was issued. But Anza wasn’t all paperwork and needle pokes. The men practiced going over the side and became awkwardly proficient descending ship cargo nets.

The men checked and re-checked their clothing issues, and ordnance teams checked and re-checked their arms. Experts from the Chemical Warfare Section marched them into their final gas chamber to check their gear, and camp staff remedied all shortages and deficiencies.

Instructors held orientation sessions on foreign customs, and languages and outbound soldiers were briefed on the rules of war. The bureaucracy put to work hundreds of clerks to make sure the Army’s paperwork was in order, and at 1600 hours, 9 December 1943, the 721st Railway Operating Battalion was generating one of the final clerical entries in its stateside file.

The men stood at attention outside the orderly room for roll call. Sergeants noted anyone absent by circling their names on the alphabetized lists. If you were present, you got a checkmark.

After completion of the Army’s final inventory came the heavy lifting. Men heaved their eighty-pound duffle bags, shouldered their twenty-pound horseshoe rolls, braced their forty-pound packs, lugged their brand new gas masks, goggles, and protective capes, straightened their wondering twelve-pound musette bags and handed off their ten-pound carbines and eleven-pound Thompson sub-machine guns to buddies as they climbed aboard the shuttle train to Wilmington.

Stumbling his way up the steep steps onto the U.S. Maritime Commission passenger car, a nameless voice in the line said to no one in particular, “Well, at least we won’t have to worry about Jap subs, boys. With all this gear, we’ll sink at the dock.”

After all the grumbling and stumbling, the men settled in, and the train whistle blew as the Camp Anza Band struck Fred Waring’s popular tune This is My Country. As the locomotive took up the slack and the train pulled slowly away, steam hissed from the boiler valves, and coal smoke descended on the tuba and French horn sections, making them disappear in a cotton-like haze. But the band played on.

Through the orange groves and vineyards, the sun faded, and the electric lights in homes revealed families at dinner. Their calmness and normalcy struck the men as oddly out-of-place, like misplaced frames in a disjointed movie reel.

It was 1900 hours, and the sun dipped on the western horizon as the troop train reached the station at Wilmington. Some soldiers had fallen asleep with their four-pound steel helmets, and plastic liners pulled over their eyes, and others were wide-awake taking in the view from the passenger car windows.

The big locomotive coaxed the train to walking speed then pulled to a smooth passenger stop under the train shed. Many of the operating craft personnel silently noted the engineer’s skill.

The soldiers detrained and formed-up in a huge galvanized steel warehouse, one of many lining the dock. Officers called out the men’s last names, and when they answered with their first and middle initial, the sound echoed like they were yelling in a giant metal cave. Dozens of call and response exchanges took place all at once as 5,000 men assembled to board the ship in a cacophony of roll.

They lined up by twos and were greeted by ladies from the Red Cross with sandwiches, coffee, and cookies. After the quick but welcome snack, and a faint foreboding that they had eaten their last meal in the U.S., they began to march from the warehouse and past rows of docked ships towards the gangway of the S.S. Mariposa.

By now, everyone was wide-awake. Heads swiveled as awe-struck young men from the Midwest and other non-coastal states cataloged their strange new surroundings – the squawking, insistent gulls, buoys gonging in the harbor and the smell of saltwater. It was the first time most of the 721st had seen ocean-going vessels and the massive equipment needed for their maintenance. These were men who, for the most part, were familiar with large industrial settings and oversized equipment, but “My God,” many thought, “These things are enormous!”

The entire coastline from Los Angeles down to Long Beach Harbor, including the embarkation point at Wilmington, was a nexus of military operations and commercial activity. It presented the Japanese with a tantalizing target.

The maritime geography of Long Beach was opportune, and its doubly protected west basin port was only minutes from the open sea. The most concentrated stretch of tempting targets ran from Long Beach up to San Pedro and proffered an enticing strip of naval bases, shipbuilding properties, repair slips, docks, wharves, Coast Guard berths, supply depots, and oil fields.

Immediately before World War II, the U.S. Congress authorized the construction of a major anchorage and set up a fleet operations base called Terminal Island Naval Dry Docks in Long Beach. The docks began working on ships in April 1942, and by August 1945, employed over 16,000 civilians. These skilled workers provided battle damage repairs and routine maintenance to tankers, cargo ships, troop transports, destroyers, and cruisers. Consolidation Steel Corporation ran an eight-way shipyard next door in Wilmington building landing craft for the Marines and other ships. They employed over 12,000. The entire area was a twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week operation, and a busy place, even without the wide-eyed men of the 721st.

As they marched in loose formation under the bows of the iron giants, one wisenheimer in the rear ranks piped, “Hey, upfront! Turn right when you see the red carpet!”

A moment later, the same guy yelled up at a seaman, mopping the forecastle of a Coast Guard cutter, “Hey, Cap’n Ahab! Swab that deck and hoist that bale! I’m coming aboard the Pequod for inspection!”

He was still giggling and mouthing an unlighted cigar, delighted at his literary reference when the soapy water from the sailor’s bucket hit squarely on his helmet. It was a well-placed shot, and the GIs around him laughed hysterically though some got splashed as well.

The chuckling men were still ribbing the wet wisenheimer when their banter was drowned out from behind by two B-17G Flying Fortresses approaching low over the docks. The deep pulsating signature of their eight 1,200-horsepower Wright Cyclone GR-1820-65 radial engines shook the pier beneath their Type I service shoes disorienting the men.

As they overflew the 721st column at less than 500 feet, the men gawked at the machine guns poking out of every conceivable surface of the plane, thirteen in all. The German Luftwaffe fighter pilots sent to intercept these monsters called the plane vier motor schreck or four-engine fear.

When the lead plane was within view of the whole column, the pilot slowly dipped the big wingtips, first the right and then the left. Then, with the low western sun glinting off their aluminum fuselages, the enormous birds banked right as if controlled by one mind and climbed into the warm Pacific sky soon out of sight. The men on the dock had no way to know, but the lead bomber was crewed and piloted by Class 5 qualified women of the U.S. Army’s Sixth Ferring Group, WASPs. They flew everything from trainers to Fortresses.

The sound of their powerful engines faded as the planes lumbered away from the waterfront. The B-17Gs were brand new on their way from the Douglas Aircraft plant in Long Beach to somewhere in the Pacific. The Long Beach Douglas plant was one of three making B-17Gs and on average, assembled four of the giant planes a day. The three plants combined turned out thirteen new bombers a day, and all were promptly put to use making rubble and carnage out of buildings and machinery and troops formerly prized by enemies.

As the aircraft passed from sight and earshot, a staff sergeant marching to the left of Company B thought to himself, “That might have been me if the railroad hadn’t jinxed things.”

The head of the column reached the gangway of the S.S. Mariposa and began climbing the long steps single file as each man’s name was read. The men below watched as their comrades disappeared into the yawning hole midship in the boat’s gray steel side.

Once inside the ship, the men were assigned quarters and told to go there and remain there until further notice. They dutifully wandered off through a maze of hatches, bulkheads, and companionways tunneling through a jungle of pipes and wiring.

Some of the lucky ones drew staterooms, but most found their ways to three-tiered bunks made of iron frames and canvas with rope slings. A few slept in hammocks built into every irregular nook and cranny of the boat. Some even had to sleep on deck in four-layer bunks protected from the wind and elements by plywood. These poor souls couldn’t even read after dark because they could use only blue lights to maintain blackout.

But all told, the men on this voyage were lucky. The Mariposa had made trips across the Atlantic, ten-day runs, where she carried twice as many men. On trans-Atlantic crossings, the soldiers shared bunks and slept in twelve-hour rotations. But the Pacific crossing was different. The men of the 721st would be at sea for a month with a brief stop in Hobart, Tasmania, for fuel and water.

A line of men not yet to the gangway eyeballed the Mariposa as they approached. They watched the twin loading masts, one astern and one on the bow, lift aboard pallets and cargo netted items. They studied the crew securing items to the deck and delivering loads into holds. It looked like a well-oiled operation, and that was heartening.

The big gray boat was longer than two football fields and had dozens of inflated life rafts tried along the railing on what looked to be the promenade deck. The inflated rafts were in addition to the wooden lifeboats mounted above the rafts on the same level as the twin smokestacks. The inflated rafts were obviously an improvised measure, and they were both reassuring and disquieting at the same time.

At 18,017 gross tons, the S.S. Mariposa was a large ship for her day. Designed by Gibbs and Cox, Inc. and built by the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation in Quincy, Massachusetts, she was launched for the Matson Navigation Company in Los Angeles in July 1931. She was laid out to accommodate 475 first-class and 229 cabin class passengers along with 359 crewmembers. On this trip, she’d be a floating home and potential Japanese target for nearly five thousand souls, including the 651 enlisted men, 21 officers, and 1 warrant officer of the 721st Railway Operating Battalion.

The S.S. Mariposa entered troop carrier service in 1941. Her two Bethlehem Steam Turbines produced 28,450 horsepower and turned twin screws that could make 22.8 knots. The Mariposa wasn’t particularly fast, but she wasn’t slow, either.

She might outrun a sub that stayed submerged, but since she wasn’t heavily armed, a sub could always surface, chase her down and shell her or submerge and launch torpedoes. Any Japanese surface vessel worth its salt would have no problem outpacing her.

The Matson Navigation Company relinquished four passenger liners for troop transport after the attack on Pearl. The Mariposa and her three sister ships, the Lurline, Matsonia, and Monterey, would complete a wartime total of 119 voyages, covering one and a half million miles to deliver over 736,000 troops. A sterling and reassuring wartime contribution. Still, in 1943, no one knew the outcome of the war, let alone the fate of a single ship on a hostile ocean.

So, if anyone aboard the S.S. Mariposa the misty morning of December 10, 1943, had somehow yet failed to grasp the grand premise to which they were now party, it all became clear as the gangway rolled back, the anchor was weighed, the mooring lines were cast, and the foghorn sounded. As tugs began maneuvering the big ship to the channel, past the submarine nets, barking seals and minefields, every man on board the crowded ship somehow felt alone.

Their passage would deliver them to a strange realm halfway around the world. The journey would be made without escort or defense, and the lumbering ship would ply waters where the enemy was active, engaged, and deadly accurate.

Overfilled with men and matériel, they would be hard-pressed to outmaneuver or outrun anyone intent on sinking them. They weren’t so much a sitting duck as a big, fat, lame Mallard with only one leg to paddle. But they were smart. They had a few tricks of their own, and they had no intention of being plucked, stuffed, and mounted on the mantel of some lucky captain of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

So, Uncle Sam wished them all bon voyage, God Speed, and recommended that they kiss any rabbit’s foot, shamrock, Saint Christopher’s medal, or Shekel that they might have handy because the odds were with the other guys on this trip. – SJH

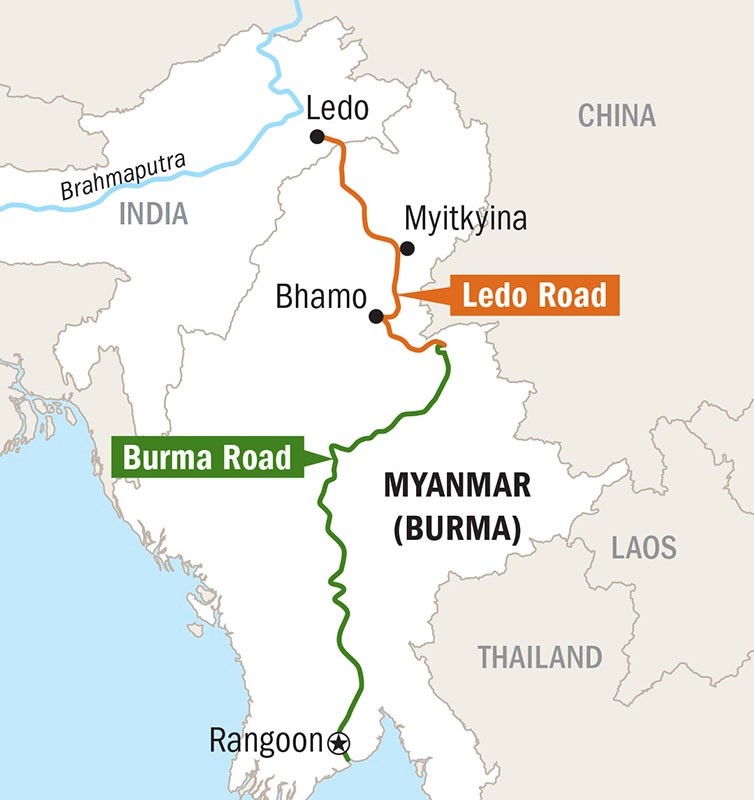

Seventy-five years ago, August 1944, Merrill’s Marauders captured Myitkyina in northern Burma eight hundred miles from where GI railroaders left them. The Marauders spent seven months in the most unforgiving jungle on earth. Their exploits are legendary. They fought thirty-two engagements including four major battles for which they were neither intended, trained, nor equipped against the entrenched, battle-hardened Japanese 18th Division. The Marauders won every time.

Then came Myitkyina. The battle lasted three months. The American victory allowed the Allies to finish the Ledo Road, secure the supply line to China, and General Slim to launch an offensive to retake Burma in December. The battle required all American hands on deck. Even men from the 721st and other railway battalions deployed to Myitkyina. Most of the 160 railroaders detailed to Burma were good men. But some volunteers were guys who were in trouble with their battalion brass; guys for whom Myitkyina was an alternative to disciplinary action. Once in Myitkyina they became the 61st Composite Group and courageously operated Jeep trains, called Bailing Wire Cannonballs, over the thirty-one miles of railroad between Myitkyina and Mogaung.

The 61st Composite Group used Jeeps for motive power because the Japanese had buried the flat rods from all but a couple of the captured locomotives. So, the resourceful GIs got busy replacing the wheels on Jeeps with rims from six-wheel-drive GMC trucks to fit the metre track gauge perfectly. Then, they chained two Jeeps together and pulled two or three flatcars loaded with troops, pipeline supplies, oil, and gas. GIs rode the flatcars to apply the handbrakes because the trusty little Jeeps had no stopping power.

To attack Myitkyina, the Marauders marched over jungle and mountain roads and paths, hacking new trails when necessary. They carried all their equipment and supplies on their backs with the help of horses and pack mules. They re-supplied by airdrops.

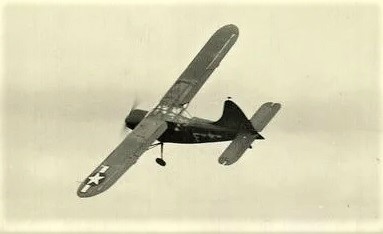

The Marauders evacuated every sick or wounded comrade. They carried casualties on makeshift stretchers of bamboo and field jackets or shirts to improvised evacuation points. These evacuation points where often remote jungle villages where the Marauders hacked out landing strips. Or, if a landing strip wasn’t at hand, they used supply drop zones, or rice paddies, or gravel bars along rivers. Brave pilots of the 71st Liaison Squadron landed and launched their sturdy Piper and Stinson evac planes in desperate conditions. The aircraft, stripped of all equipment except a compass, had room for the pilot and one stretcher — a third man onboard tempted fate.

In February 1944, 2,750 Marauders, at the peak of physical conditioning, assembled at Ledo on the Indian border and prepared to enter Burma. When they disbanded in August, they had suffered 272 killed, 955 wounded, and 980 evacuated for illness and disease. Only two of the original 2,750 survived with wounds or illness not requiring hospitalization. The following vignette is from an actual account and offered with authorial license.

My wife, Kathy, and I were honored to attend the U.S. Army’s China-Burma-India Final Round in 2005 with Rocky Agrusti, a 721st Railway Operating Battalion veteran. At our table were two Marauders who told us they had recently visited Burma. “Good grief,” I said, “You went to a country run by a military dictatorship and drug lords, with poverty and violence unrestrained? That must have been terrifying.”

The Marauder nearest me leaned in and said, “It was bad. But it was worse the first time.”

17 May 1944 – Hkumchet, State of Kachin, Burma

Corporal Harry Stevens slung his Thompson over his left shoulder and thought to himself, “Boy, I’ve seen some strange sights since I volunteered for this godforsaken outfit, but this one tops them all. God help us. This must be a first in aviation history…human catapults. If the Japs are watching, this’ll be one they’ll tell their grandchildren if I don’t kill the son-of-a-bitches first.”

A Piper L-4 Grasshopper had put down in a clearing about the size of a football field. The little airplane made the dangerous landing to evacuate a scout from I&R who had gotten badly shot up when his platoon stumbled across a Japanese machine gun nest the night before and a very ill Colonel Henry Kinnison, Jr., the unit’s commander. The clearing was soggy when the plane landed, and in the half-hour, it took to refuel and round up the wounded, a cloud burst drenched the field. Now, parked in a low spot in the clearing the plane’s main landing gear was half-submerged, and its tail-dragging third wheel was completely underwater. K Force was ready to move out, and if the Grasshopper’s passengers didn’t get help soon, they’d be goners.

Harry grabbed the side edge of the left rear wing just behind another GI. Two GIs on the other side of the airplane did the same. Four other GIs, two under each wing, pushed against the struts that ran from under the cockpit to the middle of the overhead wing.

With the pilot and the two wounded GIs aboard the rugged little plane weighed around one thousand pounds. Under normal circumstances, the L-4 would need about five hundred feet to takeoff. But nothing was normal in Burma. Harry and his buddies were there for a few more horsepower to complement the sixty-five that the Piper’s trusty air-cooled, flat-four Continental O-170 could deliver.

The GIs turned the little plane into the wind which, fortunately, was now stiff. A lanky GI in coveralls cocked the propeller and made ready to give it a spin as the pilot silently worked his checklist, “Contact, brakes, magnetos hot.”

With a thumbs-up to the GI standing in front of the plane, the pilot reached for his throttle control, and the GI gave the propeller a counter-clockwise spin. The little engine fired on the first try with a puff of blue smoke. The GI in overalls moved out of the way holding his cap on his head with his right hand. The pilot kept his feet on the brakes and advanced the throttle to the fully open position. When the RPMs hit 2,300, he released the brakes. The GIs on the rear wing ran an awkward sort of crab-shuffle and lifted the plane, raising the third wheel out of the paddy to reduce drag. The GIs in front pushed against the struts and ran as fast as they could.

They were a memorable sight with their carbines and Thompsons swinging on their shoulders and their bare asses showing through the slits they had cut in their tattered uniform trousers. Their bare asses were the sight that Harry thought the Japs might remember best.

They slit their trousers because all the GIs had dysentery and taking their pants down to relieve themselves was a waste of time and dangerous to boot. The voice of his sergeant from basic training came back to Harry now as he lifted the plane’s tail and ran sideways through the shin-deep mud tripping over the equally clumsy GI next to him, “Don’t get caught with your pants down, soldier!” Harry had heard this common chide dozens of times before volunteering for the 5307th, but it wasn’t until he started fighting in Burma that it rang true.

As the Grasshopper reached dryer ground its speed gradually outpaced that of the men’s and the GIs watched it take to the air in a sharp, steep climb out of the jungle clearing. As the little plane disappeared, Harry straightened his Thompson and stifled a humorless chuckle. – SJH

The river was muddy and wide. In the northern distance, the brick-red roof and gold weathervane atop Mount Vernon’s cupola graced its western bank. Talk about history. The window wall of the Fort Belvoir Officers Club was panoramic and the view breathtaking. This was the celebrated venue of the Saint Martin’s Military History Club, my gracious host for a Rails of War presentation.

Saint Martin of Tours, for those like myself not well-versed in Catholic hagiography, was a Roman soldier turned pacifist who embraced Christianity on the cusp of its legal ordination in A.D. 313. Martin shared his soldier’s salary with the poor, famously clothed a freezing beggar with a part of his paludamentum, his cape, and thereupon envisioned the beggar as Christ. Martin left the army, lived as an aesthetic, and founded the first monastery in Gaul, a Benedictine affair. After raising two souls from the dead with prayer, and a plethora of deserving spiritual acts, today’s canonized Martin is a patron of the poor, soldiers, conscientious objectors, tailors, and winemakers. At the Fort Belvoir Officers Club, we had the soldier demo well-covered.

Saint Martin’s membership is smart, curious, and well-versed. There was more military acumen in that room than I could muster in a lifetime. What I had working for my presentation was that the China-Burma-India theater of World War II, often referred to as “The Forgotten Theater,” was a passably novel subject matter. It was a great evening, a great dinner and a fortunate introduction to new friends and old surroundings.

Fort Belvoir, nine miles south of our home in Alexandria, is in our backyard. First used in 1915 as a construction and engineering center it is today, much larger, more mission-diverse, and presently attuned to research and technology, some of which can be publicly acknowledged. But, for my money–and that’s a literal statement because we are supporters–what is yet to come is most interesting.

Fort Belvoir will be the home of the National Museum of the United States Army. Construction is underway on eighty-four acres with a planned opening in 2020. The museum will be grand, guaranteed. I’m happy for the Army, those who served, and our nation, but it will mean more traffic in our neighborhood, a preoccupation in the D.C. Area. If you’d like to support the museum, follow the link. They make it easy and offer a level for every contributor. So, thanks again to the Saint Martin Military History Club for the invitation to talk about Rails of War and thanks to the men and women of Fort Belvoir for their service and dedication. Therein lie countless stories yet told and I humbly encourage everyone who came to me with the question, “How do you write a book?” to find out as I did, begin by telling the story. – SJH

Happy people, I didn’t see a scowl all weekend, Buddha all. And, before I offend Buddhists, I use nirvana in an unexamined way, a colloquial synonym for Christian heaven. But, as true Buddhists know, nirvana is the extinction of desire, and in that sense, the Amherst Railway Hobby Show is the opposite. The show is an irresistible inducement to material lust. Any and all railfan hobby stuff can there be purchased in one of the four expansive pavilions that draw upwards of 45,000 paying entrants over two days. Thus, the show is more like wafting a dish of Gifford’s ice cream under the nose of a newly sugar-free devotee during Lent.

The attendees were a determined lot. At nine o’clock sharp, on a cold and snowy Saturday morning, they flooded the entrances after queuing outdoors for who knows how long. The massive parking lot of the Big E was nearly full when we arrived early. By the way, the Big E, also known as the Eastern States Exposition, is a not-for-profit with a board drawn from all six New England states. It’s huge. The Big E is the West Springfield, Massachusetts home of the New England Fair. (Not a state fair.) At the Big E, all of New England gets to show. Every September you can visit and get your fill of sheep shearing, deep-fried cheesecake, maple syrup, and cotton candy. Last year’s total attendance was 1,543,470. Who knew?

Rails of War displayed near the Dunkin Donuts outlet in a sea of vendors selling every miniature railroad artifact under the sun. Kathy was amazingly patient and supportive. She gave up our usual warm-and-sunny-spot-vacation timeslot to follow me to West Springfield in late January to talk railroad. Yes, I married well. I started a hundred conversations with, “Rails of War is the story of my father’s railroad battalion in World War II. The 721st operated in the China-Burma-India theater in present-day Bangladesh.” Then, nine times out of ten the person to whom I was talking would launch into a story about a relative who served in World War II or confess that he or she was an avid history buff as well as a railfan.

And so it went. For two days. We sold books with the proceeds going to the Amherst Railway Society, and we met many colorful and connected folks. In the crass world of commercial publishing, the weekend was platform development. In my world, it was meeting a bunch of new people.