Lore and More

From The Tide of Deception: Mystery on the Coast of Maine

by Steven James Hantzis

Ovens Mouth, Boothbay, Maine

We love our house on Barters Island, and we’re lucky enough to have deep water. We keep our 25-foot C-Dory, Catleen, on our float. One of the easy-to-get-to destinations, only minutes away, is a narrow passage called Oven’ Mouth. Through this thousand-yard gut, tidal currents fill and empty a sizable estuary of Back River. At its narrowest, the passage between land reduces to 150 feet, and the navigable channel is even narrower. The current runs six knots with the changing tides. When piloting a boat and traveling with the current, your speed must be faster than the current to maintain control of your vessel. Otherwise, you become buoyant debris at the hydrologic whims of nature.

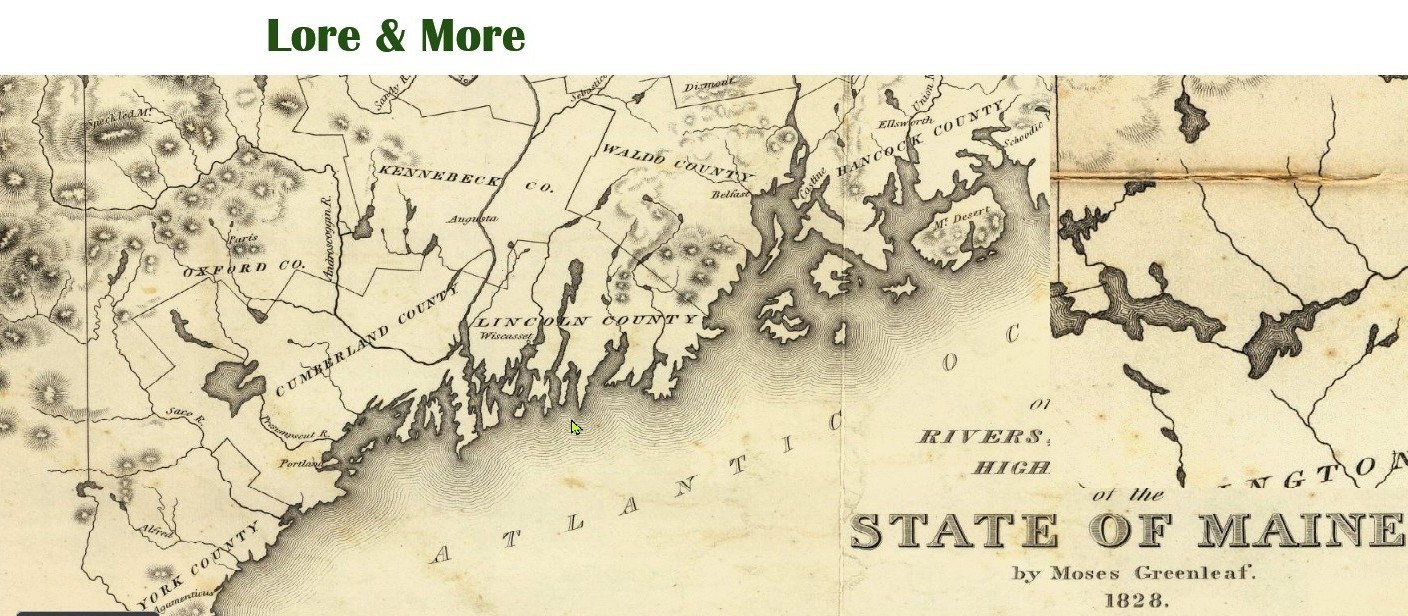

Wabanaki Native Americans used Oven’s Mouth as a shortcut between the Damariscotta and Sheepscot Rivers in pre-colonial times. They paddled birchbark canoes down the Damariscotta, then portaged west through the pines and oaks across what is now the Dolphin Mini Golf attraction. At Oven’s Mouth, they paddled to the chilly Sheepscot. This route saved them the longer journey via the choppy mouth of the Damariscotta, across broad Boothbay Harbor, then through Townsend Gut to the Sheepscot. Along their journey, these hunter-gatherers foraged through varied eco-cultures, enjoying the buffet.

Maine has a long history of getting places by water. Water was conveyance long before roads. Overwater moved the shore’s bounty: deer and beaver pelts and luxurious hides of marten, otter, ermine, fisher, and fox. Intricate brown ash basketry and other barterable items made their way to Native American markets along the free-flowing streams, rivers, and coastal routes. When Europeans arrived, water moved the men and ships, who enforced new rules of trade.

For the Wabanaki, Oven’s Mouth was more than just a shortcut. It was a sacred place, a place of spirits that protected and guided them. As they paddled in the narrow channel to the Sheepscot, they sang songs of gratitude to the spirits, the earth, and the water.

On September 9, 1777, as the sun dipped beyond the western shore of the Sheepscot, a clan of Wabanaki hunters pulled their canoes through a muddy flat. Wading in muck to their knees, they reached shore on the northern tip of Barters Island. All were wary of the uncertain sky, turning leaves, and an approaching storm. As they paddled through Oven’s Mouth, their laughter and songs echoed off the rocky walls. But when they reached the wider Cross River, they saw something that upset their absorbing rhythm.

HMS Rainbow sets off on her 15-mile trek upriver into hostile territory during the American Revolution. It was a high-risk passage against both the elements and the odds, but her indefatigable captain deemed it “a military necessity.” Geoffrey Hunt, Trouble Heading for Wiscasset: H.M.S. Rainbow in the Sheepscot River, Maine, 10th September 1777 (Private Collection) US Naval Institute

A ship approached, her three topsails luffing in the confused wind. Only the small sails fore and aft billowed. Men scrambled on the yardarms, reefing the lower sails. The hunters knew European ships. White men had plied Wabanaki waters for more than a century. But this one was different. The men on the top decks wore red coats, and the pennant flying astern told the Wabanaki this was the British tribe. This ship was bigger and more heavily armed than any they had seen before. The Wabanaki counted twenty-two gunports on her starboard side, with the lower ports battened to thwart the churning chop. The men aboard looked hard and fierce, and the Wabanaki were lucky to be ashore and protected. The spirits were pleased.

The hunters watched the ship pass and wondered where she was going. Was she lost? She was too large for the passage, and there was no settlement or European encampment in her direction. The nearest British town was Wiscasset, five miles to the north on the main channel of the Sheepscot.

Aboard the HMS Rainbow, Sir George Collier, captain and acting commodore of the British Royal Navy forces in Halifax, came to the same conclusion. Night approached, and the storm began. Captain Collier was an aggressive, tested commander. But he was now responsible for a British ship of the line floundering in unknown water, amid rocky ledge, submerged hazards, sucking mudflats, and an unforgiving tidal flow. The local fisherman, impressed as a pilot in Boothbay Harbor, claimed to be a royalist. He claimed to know the route to Wiscasset, where the mast-ship Gruel was loading its nautical contraband for a trip to France. That was Captain Collier’s mission. Take or destroy the Gruel. Now he suspected his involuntary pilot to be an American militia sympathizer. His compass reading didn’t lie. They were sailing east, not north. He would not allow the Rainbow to founder. He called the order, “Cut the lashings on the ‘best bower’ to the starboard foremast channel. We will anchor here. Douse any sails reefed or still set.” Thus, the outsized Rainbow at 133 feet along her waterline, and drafting twenty feet, set anchor in the narrows of Oven’s Mouth.

Amid the endless Maine frontier in 1777, countless white pine trees towered to perfection. The British and the French marveled at their utility for nautical construction. Both nations had depleted their native forests of oak and other suitable timber. Maine’s prized specimens rose forty feet or more and measured forty inches in diameter at their flawless trunks. Turned by the hands of journeymen, these ‘sticks’ became masts, bowsprits, topmasts, yards, and spars at the Halifax Naval Yard or one of six Royal Navy Dockyards in England. They were perfect for masting the brutes of the sea, ships of the line, the vessels that decided battles, blockades, and the fates of nations.

Continental wars blocked British access to Baltic timber in the 1650s. And even with access, Baltic trees were seldom more than twenty-seven inches in diameter. So, King William III appointed a surveyor general for New England. The surveyor’s minions tramped the virgin forests and marked ramrod pines greater than twenty-four inches with three axe strikes in the symbol of a broad arrow. These were the king’s pines. This possessive insult enraged the American colonists. The British applied severe penalties for stealing these pines, skirmishes erupted, and a black market flourished. In 1772, colonists revolted in Weare, New Hampshire. Early in the morning, after an overnight rally in a local tavern, townspeople blackened their faces. They set upon a dozing sheriff and his deputy and whipped them senseless with switches. The rioters shaved the manes and tails of the lawmen’s horses. They even severed the poor beasts’ ears, then mounted the sheriff and deputy to ride out of Weare down a gauntlet of the aggrieved. Colonial resentment smoldered as the Pine Tree Riot predated the Boston Tea Party by a year and a half.

By 1777, with the colonies in full revolt and the French backing their rebellion, the British needed masts. These strategic components in the hands of the French would be doubly damaging. The intelligence possessing Captain Collier as he advanced up the treacherous Sheepscot was that a suspected mast shipment was making ready north of Wiscasset, bound for Cherbourg.

In the early hours of September 10, Captain Collier ordered the launch of two of the Rainbow’s cutters, the smaller boats for transporting the Royal Marines. He ordered a cutting-out raid on the Gruel, and a hundred marines and sailors set off from Oven’s Mouth under the cover of darkness and rain. Cutting out was the term for commandeering an enemy vessel, in this case, the Gruel. The two cutters snuck past the sleeping village of Wiscasset. Then the raiders rowed north on a flood tide where, according to the impressed fisherman now with the raiders, the Gruel was loading her contraband.

When dawn broke on the Rainbow, Captain Collier saw how close they had come to disaster. The ship could barely swing on her hawser without grounding. Collier launched the remaining cutter, and with deft seamanship, the cutter’s crew wrapped the ship out of its predicament and into the main channel of the Sheepscot. By early afternoon, the Rainbow anchored off Wiscasset Point, positioned to level the town with cannon fire.

Worried locals breathed easier when Captain Collier sent a party ashore under a flag of truce. Collier’s emissary delivered a letter to the local magistrate demanding the surrender of two small cannons and the contraband pines he believed to be loading nearby. Thus, negotiations began with the exchange of letters.

The two cutters arrived at the Gruel near sunrise. The Royal Marines surprised the Gruel’s master, boatswain, and two mates and took them prisoner without a shot or saber slash. After securing the mast-ship, they brought a three-pound cannon aboard and barricaded the boat’s deck with planks already aboard the Gruel. They were ready to return their prize. But they needed a favorable tide, a slack tide just beginning to ebb to clear the shallows and mudflats of the sinuous Sheepscot.

The Gruel’s cook, returning to the boat from shore, saw the capture and ran to tell the local militiamen’s quartermaster. By nine o’clock, the Lincoln County Regiment of Militia, 150 Sons of Liberty, lined the shore and began pelting the raiders with musket and cannon fire. Trapped by the ebbing tide, the raiders were powerless to wrap the Gruel into the river channel. The raiders hunkered down behind their plank armament. Around noon, a second cannon arrived and pulverized the improvised palisade aboard the Gruel. The raiders were in a tough spot.

Captain Collier grew concerned around sunset and launched the remaining cutter. However, the boat returned, fearing an ambush upriver. They were right.

The raiders were running out of options. The Gruel was too large to maneuver down the twisty river. The cutters would have to wrap her off her mooring and tow her to deep water. At ten o’clock, with the moon setting, a raiders’ detachment shoved some of the mast and spars into the river and holed the mast-ship. Then they snuck aboard their cutters in the Gruel’s lee and started downriver. But the Sons of Liberty were waiting. The raiders’ flight stalled when they encountered a boom pulled taunt across the river by the militiamen. The raiders were lucky to hack their way through the heavy rope and out of danger with only one man injured by militia fire. At eleven o’clock, the first cutter hove up along the Rainbow. Captain Collier recovered all the raiders, their prisoners, and both boats by midnight. But the wind was against them as the militia massed at Wiscasset Point.

Negotiations continued while the Rainbow waited for an ebbing flood tide and a favorable wind. Collier bluffed and told the Sons of Liberty they had one hour to evacuate Wiscasset before he opened fire to level the town. It bought him time. Finally, with favorable sailing conditions arriving in the early hours of September 12, Collier relented. He released the prisoners onto a small, commandeered schooner for a promise of safe passage as the Rainbow navigated the Sheepscot narrows.

The Rainbow’s raid on Wiscasset was a measured success. They recovered three main masts and one mizzenmast. The raiders decommissioned the mast-ship and denied the French important contraband. Rainbow suffered only one man wounded. Sir George Collier entered history books as a successful, daring naval officer. He won a major victory against the colonialists in the 1779 Battle of Penobscot Bay.

The fisherman, though, that’s who interests me. Therein lies the lore.

François Arsenault was the fisherman, but he told the British he was Samuel Jones. He was a linguistic chameleon and spoke the English of the colonists, his mother’s tongue. They never suspected he was French. The disdainful British looked down on the colonial dialect and lumped François into the heathen herd.

François was nineteen years old and unmarried. He towered over most other fishermen. His light beard framed his handsome features. He wore rough, sea-worn clothes, and his dark hair flowed from beneath his knit cap pulled low against the Gulf of Maine chill. He was three weeks engaged to Danielle from Monhegan Island.

François was smart. Born and raised on the coast of Maine on the island of Southport, he had learned much in his years fishing with his father. He knew the water, and the vessels that sailed it. But he had never seen a ship the size and menace of the HMS Rainbow. He squinted to make out the detachment of Royal Marines approaching in a cutter. The British were ruthless, and François feared impressment or punishment for disobeying their orders. He thought of Danielle on Monhegan’s Pebble Beach, propped on a worn wool blanket, watching seals cavort on the ledge near shore. Her soft auburn curls danced on her lithe shoulders when she laughed. He would do anything to be with her again.

Six sailors oared the cutter with a coxswain at the stern. It surprised François how fast the boat moved through the chop. Perfectly synced long oars propelled it like a water strider on a pond. Four grim, musket-toting marines stood in the bow of the eight-meter boat, their red coats fluttering in the building nor’easter. Bayonets dangled on their cross belts. François’s single-masted fishing skiff could neither outrun them nor defend against them. He had just set sail for Boothbay when the Rainbow appeared on the horizon.

The British would take no quarter with a Frenchman. So, when the older marine hailed him, he answered in English, “Yes, I fish the Sheepscot. I have fished as far north as the reversing falls above Wiscasset Point.”

The solemn marine declared, “In the name of His Majesty King William III, I order you to come with us. Secure your skiff here and come aboard.”

François hesitated, then waved at the approaching front and pleaded, “But, my lord, my boat may swamp in the coming gale. If I lose my boat, I cannot make a living.”

The pitiless soldier sneered, his words as cold as the murky depths, “If you do not do as I order, you will have no need to make a living.”

A fearful and overwhelmed François played out his anchor, obeyed the order, and began living a lie to save his life.

As a little girl growing up on the coast, she listened to the lore at family gatherings. These get-togethers of thirty or more boisterous relatives always made her smile and laugh. The men built a raging fire in a pit on the rocky shore. Then, in a flame-marred kettle, they boiled lobsters in a stew of salty Atlantic, seaweed, clams, cut potatoes, whole onions, corn on the cob, and hard-boiled eggs. They drank beer and coffee brandy and told stories from the dismal past. They told how François escaped from British servitude, and his subsequent move to Monhegan. Monhegan was French-controlled territory and had been since 1689. With the end of the French–Indian War in 1763, Monhegan became France paisible.

François was with the British when they took the Gruel. He withstood the Sons of Liberty’s bombardment. When the detachment from the Rainbow snuck from the Gruel back to their cutters under fire in the darkness, François parted company in the chaos. On the river’s bank, the militiamen identified him as a friend. Lucky for him. The quartermaster recognized François and vouched for him. Fearing the British might track him and hang him for desertion, François retrieved his skiff and sailed for Monhegan a day later. He and Danielle married on Christmas Eve 1777, and over the next thirty-nine years together, they raised eight healthy, intelligent children with love, hard work, and good fortune. Not a day passed that François did not thank God for allowing him to escape the British and marry Danielle.

Note: It’s well documented that a fisherman was forced into military service by the British in Boothbay Harbor, but what happened next is lost to history. The post-impressment life of François is fiction. In The Tide of Deception, François becomes the familial anchor for my seven-generations-later protagonist, Sandy. Sandy is a single mother of a precocious seventeen-year-old daughter and a senior researcher at Bigelow Laboratory. Sandy is preoccupied with a rogue tide that pounded Boothbay Harbor on October 28, 2008. Her obsession leads her into unforeseen circumstances. And yes, the Boothbay Harbor mystery tide is real.