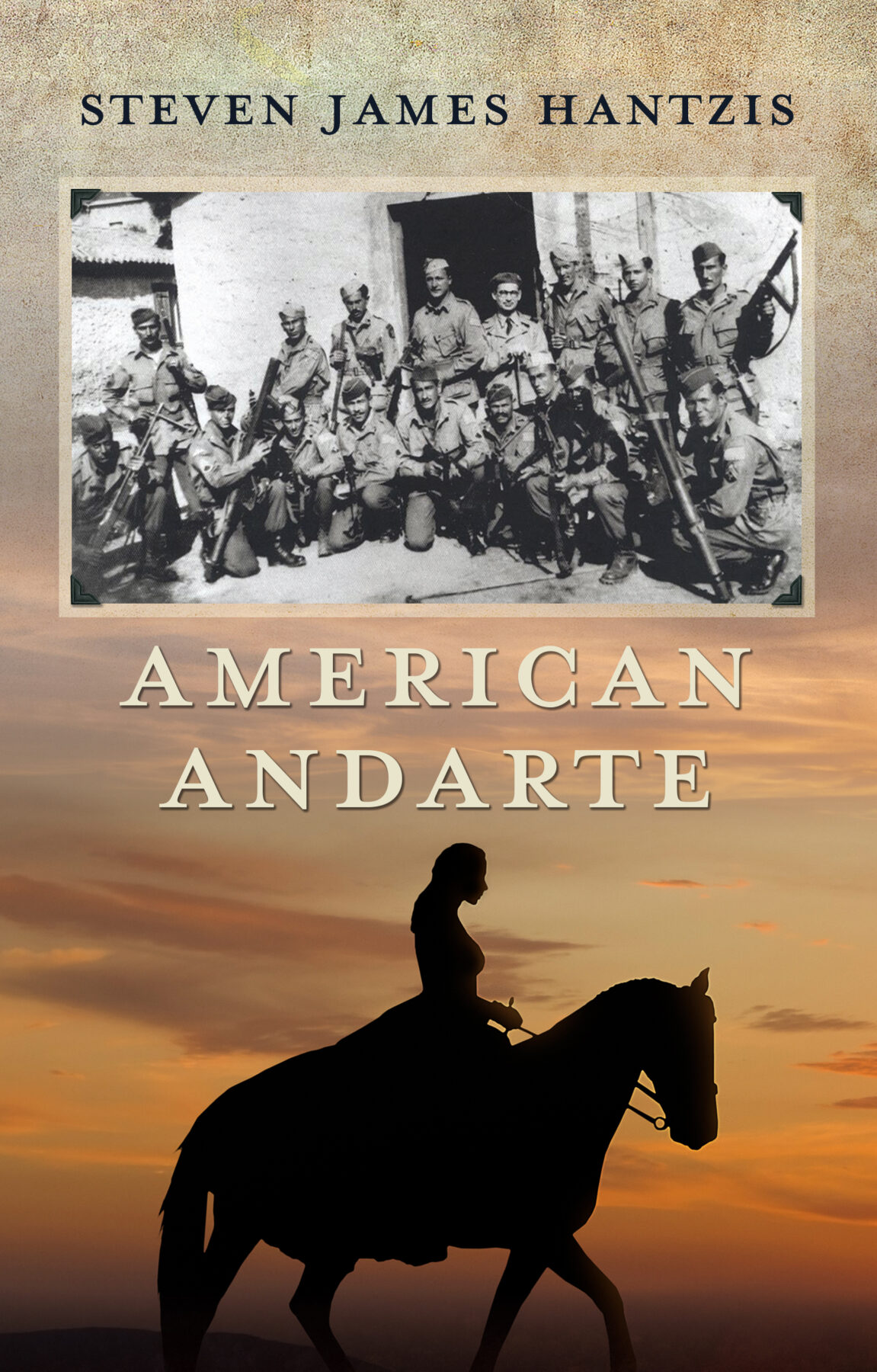

I am pleased to announce the launch of American Andarte: An OSS Commando Fights for Greece, available through many sellers in eBook and paperback. For those who read The Greek Boxer, Book #1 in my series, “The Greek Stories,” thank you. The two books have different settings and tones. The Greek Boxer is told in an “Old Country” tone and reflects the oppression and hardship, and challenges of the first generation of Greek immigrants in America. American Andarte advances a generation and strives for a modernistic, can-do, World War II tone. The second generation of Greeks, like my protagonist, Stavros, has benefited from the success and drive of their forefathers and foremothers. They are educated, more integrated, and determined to live the American Dream. Yet, they too face societal resistance and maintain an intractable cultural identity, a haven from which to organize, network, worship, and fight as they must against prevailing headwinds. That identity, broader and more dispersed, lives on today in the Greek American landscape, and I am proud to be a small part of it.

I am pleased to announce the launch of American Andarte: An OSS Commando Fights for Greece, available through many sellers in eBook and paperback. For those who read The Greek Boxer, Book #1 in my series, “The Greek Stories,” thank you. The two books have different settings and tones. The Greek Boxer is told in an “Old Country” tone and reflects the oppression and hardship, and challenges of the first generation of Greek immigrants in America. American Andarte advances a generation and strives for a modernistic, can-do, World War II tone. The second generation of Greeks, like my protagonist, Stavros, has benefited from the success and drive of their forefathers and foremothers. They are educated, more integrated, and determined to live the American Dream. Yet, they too face societal resistance and maintain an intractable cultural identity, a haven from which to organize, network, worship, and fight as they must against prevailing headwinds. That identity, broader and more dispersed, lives on today in the Greek American landscape, and I am proud to be a small part of it.

I posted About American Andarte on my author blog if you’d like a glimpse into the book. But before I sign off, I’d like to praise my Alinet, LLC publishing team; they don’t get enough credit, and that’s my fault. Jennifer Caven is my editor and foremost external critic. She’s relentless, and her changes and suggestions make it look like I can write. Elizabeth MacKenney designs my covers and transforms my half-baked ideas into honest-to-God art. Nancy Coffman at NC Strategic Solutions manages my website and media, along with the good folks at Websults. — SJH

American Andarte will launch on January 30, 2026. It’s a long book, roughly 430 pages, minus endnotes, photographs, bibliography, maps, and an acronym key. I apologize to anyone expecting the industry standard 230-page issue. It’s a big story to tell.

American Andarte will launch on January 30, 2026. It’s a long book, roughly 430 pages, minus endnotes, photographs, bibliography, maps, and an acronym key. I apologize to anyone expecting the industry standard 230-page issue. It’s a big story to tell.

The first part of the book will introduce you to Stavros, the protagonist, and his family. It’s 1957, and the family is parsing an obligation of honor carried forward from a generation before. When Stavros returns to his home, his thoughts and the storyline flash back to World War II. Stavros is a babe in arms during the first book of the series, The Greek Boxer. When Pearl Harbor strikes, he’s of military age but deferred because of his teaching position at Park College in Kansas City, Missouri. He relinquishes his deferment and enlists in a special US Army unit called the Greek Battalion.

Stavros is off to training, first in the Greek Battalion, then as an Office of Strategic Services (OSS) commando. You can easily access the sources in my notes and bibliography, documenting this section. The government kept OSS operations in Greece during World War II top secret until recently. Also, only a few OSS veterans wrote or spoke about their experience. You’ll find these sources listed in the bibliography. Thus, their training in the US Army, OSS, and transport to theater is largely nonfiction.

Speaking of nonfiction, American Andarte backgrounds the reader in events that happened before the Americans arrived in theater in 1944. The Greeks began resisting following the Italian invasion of 1940. The Greek army and andartes defeated the Italians, pushed them back into Albania, and that’s why the Germans came to the Italians’ rescue in the spring of 1941. British commandos parachuted into Greece in the fall of 1942 and began operations and coordination with local andartes. They were successful in critical sabotage missions and political juggling among the Greeks well before the Americans arrived. Most importantly, for American Andarte, the two British commanders, Eddie Myers and Christopher Woodhouse, wrote compelling books about their time in Greece. Amazing stories.

Once Stavros and his Operational Group (OG) land in Greece, the story moves on two axes. The first is military, how the OG operates, how they coordinate with the local andartes, tactics, weapons, and strategy. The fictional missions in the book are composites of real-life missions. The second storyline is more personal. It is less about Stavros the leader and more about Stavros the man. The Americans work with the Greek andartes, led by a captivating woman named Dimitra. Slowly, perhaps awkwardly, a relationship develops between the two leaders, two very different people with unique backgrounds. The story of Dimitra illustrates much about the role of women in Greece during the occupation. Dimitra and Stavros are both educated, and their dialogue and relationship let the reader glimpse a complex world.

And here’s a note on the dialogue, especially the common usage dialogue among the Greek locals and andartes. It may seem stilted, but the style of speech comes straight from the two books by Woodhouse and Myers, who captured the Greek informalities and idioms, and I trust the reader will catch on.

The ending, well, you can judge for yourself. Please remember that there are two more books in the series: Wolf Pelt and Fifty-Seven. – SJ Hantzis

The ending, well, you can judge for yourself. Please remember that there are two more books in the series: Wolf Pelt and Fifty-Seven. – SJ Hantzis

One of many things the American OSS commandos in Greece found unusual was the incorporation of female fighters into the armed resistance against the Nazis. The largest Greek resistance organization, EAM-ELAS, which the Americans fought alongside, was left-led and encouraged women to fight and to vote within its ranks. In American Andarte, Stavros, the protagonist and leader of his OSS Operational Group, is assigned to coordinate with an EAM-ELAS unit led by the captivating Dimitra. Her story will enlighten readers about the challenges women confronted during the occupation. Dimitra, having been active in the resistance for longer, is more seasoned than the Americans, whom she often declares bewildering.

In the following vignette, Stavros and a combined column of OSS Commandos and Greek andartes enter a village on the way from Parga, their landing on the west coast of Greece, to Chomori, where they will find quarters. Stavros spots something unusual. He asks the leader of the Greek andartes about the oddity.

***

On the afternoon of the third day, the fighters forded the Achelous River and stopped in the village of Loutra. The spring rains had filled the river’s banks, and the fifty meters of submerged rock pathway proved treacherous. The men lifted their weapons, packs, and sleeping bags above their heads and waded. Everyone except those riding horses was soaked to their belts. In Loutra, Stavros noticed the women wore dresses pinned on their right shoulders. He asked Yiorgos.

“They pin their dresses so that the Germans won’t rip and tear them as they have before. The Germans check their shoulders for bruises. They see a bruise . . . they shoot the woman. Or hang her or detain her. The bruises are proof to the Germans that they fired rifles. The only women firing rifles are andartes and reserves.” — SJ Hantzis

How did I choose the settings for my four-book series, The Greek Stories? Greece has an interminable history with infinite inflection points. So, yes, it was tough, but not actually. My family’s history in America starts a few years before the first book, The Greek Boxer. My grandfather and fictionalized protagonist, Harry Hantzis, came to America in 1906 with his brother. He returned to Greece in 1912 to fight in the First Balkan War. His return to America in 1914 coincides with the Great Colorado Coal War, the bloodiest episode in American labor history and the historical reference for the book. Although my grandfather, to my knowledge, never traveled to Colorado, an obligation of honor sets my fictional grandfather upon this path. The Greek Boxer is a study of honor and obligation.

How did I choose the settings for my four-book series, The Greek Stories? Greece has an interminable history with infinite inflection points. So, yes, it was tough, but not actually. My family’s history in America starts a few years before the first book, The Greek Boxer. My grandfather and fictionalized protagonist, Harry Hantzis, came to America in 1906 with his brother. He returned to Greece in 1912 to fight in the First Balkan War. His return to America in 1914 coincides with the Great Colorado Coal War, the bloodiest episode in American labor history and the historical reference for the book. Although my grandfather, to my knowledge, never traveled to Colorado, an obligation of honor sets my fictional grandfather upon this path. The Greek Boxer is a study of honor and obligation.

From 1914, I leap ahead to a most interesting time, World War II. My protagonist, Stavros, grows from a babe in arms in The Greek Boxer, into a military-aged male who joins a specialized U.S. Army unit, the Greek Battalion. Then after its disbandment because of political pressures, Stavros volunteers for an Office of Strategic Services (OSS) commando group to fight in Greece alongside the local resistance, the andartes. American Andarte is both history and fiction. Until recently, the government classified the exploits of OSS commandos in Greece as top secret, and few people wrote about them. I was lucky to be tipped off about this incredible US Army battalion and subsequent OSS campaigns by a dear friend with strong ties to our military.

Sticking with my protagonist for the final two books in the series, Stavros is now a CIA operative in Greece. In 1951, Greece was rife with espionage from every quarter. Greece and Turkey are on the cusp of NATO ascension. The freshly minted CIA is flush with untraceable money and little accountability. The British are broke and hand off their mole-ridden campaign to overthrow the communist regime in Albania to the CIA, who name it Operation Fiend and run it from Greece. The title for book #3, Wolf Pelt, comes from Homer’s account of the Trojan War, the Iliad. In that epic poem, Dolon, a spy for Troy, sneaks among the Greeks at night wearing a wolf’s pelt for disguise. Great Odysseus discovers him with predictable consequences.

Book #4, Fifty-Seven, moves the timeline up to 1957. The Soviet Union had just launched Sputnik, catching America off guard and far behind. America had, however, launched a nuclear-powered submarine, the USS Nautilus (SSN-571), in 1956. But America had no place to refuel and maintain the boat except Groton, Connecticut, a long sail from the critical theater of the eastern Mediterranean. The Greeks step up and undertake an ambitious refit of an old shipyard to meet the needs of its NATO partners. Of course, the communists are lurking, and Stavros, now at CIA headquarters, returns to Greece to ferret out the troublemakers. His long-time love interest, Dimitra, is there, as is Stavros’s running companion, Christakis, who is undercover in Enosis, the militant movement to free Cyprus from British control.

These four settings are, in my estimation, under-reported but exciting, and consequential. Anyone who wants more details can read through my bibliographies and notes included in all four books. As always, I write fiction, but I love to anchor my fiction in genuine history.

I hope you enjoy The Greek Stories and find them entertaining and educational. Here’s to your delight; may you enjoy reading these books as much as I enjoyed writing them. — Steven James Hantzis.

Release dates

The Greek Boxer November 25, 2025

American Andarte January 15, 2026

Wolf Pelt March 15, 2026

Fifty-Seven May 15, 2026

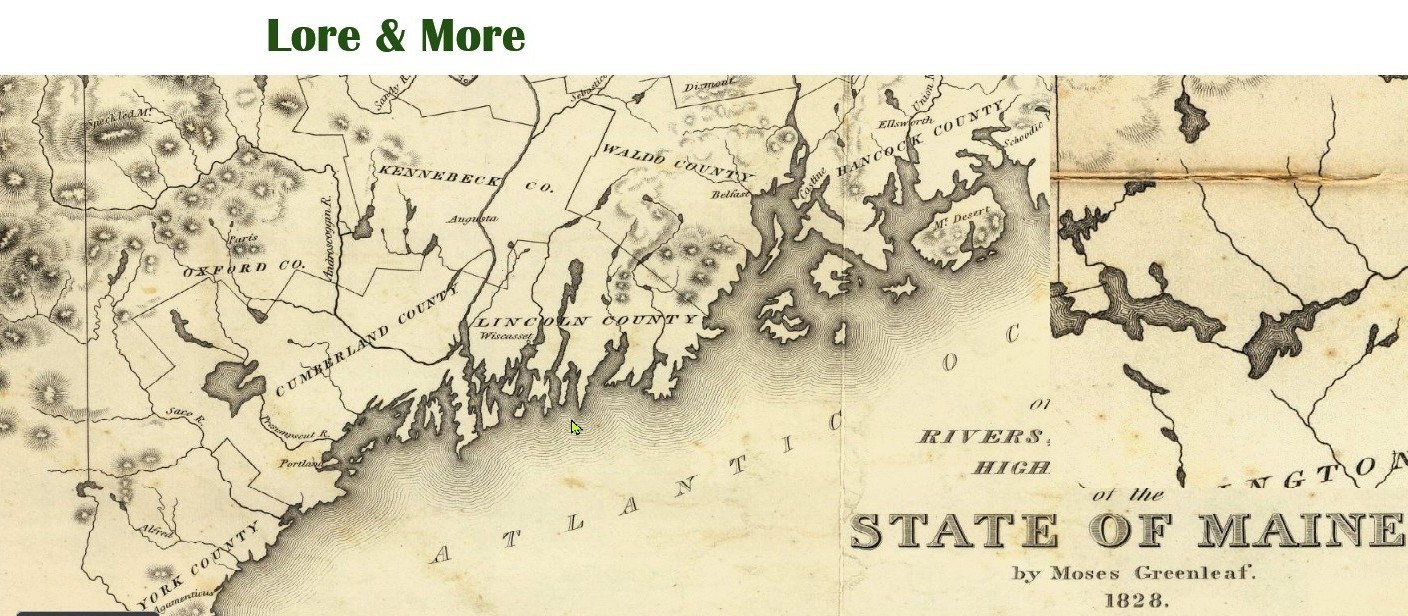

From The Tide of Deception: Mystery on the Coast of Maine

by Steven James Hantzis

Ovens Mouth, Boothbay, Maine

We love our house on Barters Island, and we’re lucky enough to have deep water. We keep our 25-foot C-Dory, Catleen, on our float. One of the easy-to-get-to destinations, only minutes away, is a narrow passage called Oven’ Mouth. Through this thousand-yard gut, tidal currents fill and empty a sizable estuary of Back River. At its narrowest, the passage between land reduces to 150 feet, and the navigable channel is even narrower. The current runs six knots with the changing tides. When piloting a boat and traveling with the current, your speed must be faster than the current to maintain control of your vessel. Otherwise, you become buoyant debris at the hydrologic whims of nature.

Wabanaki Native Americans used Oven’s Mouth as a shortcut between the Damariscotta and Sheepscot Rivers in pre-colonial times. They paddled birchbark canoes down the Damariscotta, then portaged west through the pines and oaks across what is now the Dolphin Mini Golf attraction. At Oven’s Mouth, they paddled to the chilly Sheepscot. This route saved them the longer journey via the choppy mouth of the Damariscotta, across broad Boothbay Harbor, then through Townsend Gut to the Sheepscot. Along their journey, these hunter-gatherers foraged through varied eco-cultures, enjoying the buffet.

Maine has a long history of getting places by water. Water was conveyance long before roads. Overwater moved the shore’s bounty: deer and beaver pelts and luxurious hides of marten, otter, ermine, fisher, and fox. Intricate brown ash basketry and other barterable items made their way to Native American markets along the free-flowing streams, rivers, and coastal routes. When Europeans arrived, water moved the men and ships, who enforced new rules of trade.

For the Wabanaki, Oven’s Mouth was more than just a shortcut. It was a sacred place, a place of spirits that protected and guided them. As they paddled in the narrow channel to the Sheepscot, they sang songs of gratitude to the spirits, the earth, and the water.

On September 9, 1777, as the sun dipped beyond the western shore of the Sheepscot, a clan of Wabanaki hunters pulled their canoes through a muddy flat. Wading in muck to their knees, they reached shore on the northern tip of Barters Island. All were wary of the uncertain sky, turning leaves, and an approaching storm. As they paddled through Oven’s Mouth, their laughter and songs echoed off the rocky walls. But when they reached the wider Cross River, they saw something that upset their absorbing rhythm.

HMS Rainbow sets off on her 15-mile trek upriver into hostile territory during the American Revolution. It was a high-risk passage against both the elements and the odds, but her indefatigable captain deemed it “a military necessity.” Geoffrey Hunt, Trouble Heading for Wiscasset: H.M.S. Rainbow in the Sheepscot River, Maine, 10th September 1777 (Private Collection) US Naval Institute

A ship approached, her three topsails luffing in the confused wind. Only the small sails fore and aft billowed. Men scrambled on the yardarms, reefing the lower sails. The hunters knew European ships. White men had plied Wabanaki waters for more than a century. But this one was different. The men on the top decks wore red coats, and the pennant flying astern told the Wabanaki this was the British tribe. This ship was bigger and more heavily armed than any they had seen before. The Wabanaki counted twenty-two gunports on her starboard side, with the lower ports battened to thwart the churning chop. The men aboard looked hard and fierce, and the Wabanaki were lucky to be ashore and protected. The spirits were pleased.

The hunters watched the ship pass and wondered where she was going. Was she lost? She was too large for the passage, and there was no settlement or European encampment in her direction. The nearest British town was Wiscasset, five miles to the north on the main channel of the Sheepscot.

Aboard the HMS Rainbow, Sir George Collier, captain and acting commodore of the British Royal Navy forces in Halifax, came to the same conclusion. Night approached, and the storm began. Captain Collier was an aggressive, tested commander. But he was now responsible for a British ship of the line floundering in unknown water, amid rocky ledge, submerged hazards, sucking mudflats, and an unforgiving tidal flow. The local fisherman, impressed as a pilot in Boothbay Harbor, claimed to be a royalist. He claimed to know the route to Wiscasset, where the mast-ship Gruel was loading its nautical contraband for a trip to France. That was Captain Collier’s mission. Take or destroy the Gruel. Now he suspected his involuntary pilot to be an American militia sympathizer. His compass reading didn’t lie. They were sailing east, not north. He would not allow the Rainbow to founder. He called the order, “Cut the lashings on the ‘best bower’ to the starboard foremast channel. We will anchor here. Douse any sails reefed or still set.” Thus, the outsized Rainbow at 133 feet along her waterline, and drafting twenty feet, set anchor in the narrows of Oven’s Mouth.

Amid the endless Maine frontier in 1777, countless white pine trees towered to perfection. The British and the French marveled at their utility for nautical construction. Both nations had depleted their native forests of oak and other suitable timber. Maine’s prized specimens rose forty feet or more and measured forty inches in diameter at their flawless trunks. Turned by the hands of journeymen, these ‘sticks’ became masts, bowsprits, topmasts, yards, and spars at the Halifax Naval Yard or one of six Royal Navy Dockyards in England. They were perfect for masting the brutes of the sea, ships of the line, the vessels that decided battles, blockades, and the fates of nations.

Continental wars blocked British access to Baltic timber in the 1650s. And even with access, Baltic trees were seldom more than twenty-seven inches in diameter. So, King William III appointed a surveyor general for New England. The surveyor’s minions tramped the virgin forests and marked ramrod pines greater than twenty-four inches with three axe strikes in the symbol of a broad arrow. These were the king’s pines. This possessive insult enraged the American colonists. The British applied severe penalties for stealing these pines, skirmishes erupted, and a black market flourished. In 1772, colonists revolted in Weare, New Hampshire. Early in the morning, after an overnight rally in a local tavern, townspeople blackened their faces. They set upon a dozing sheriff and his deputy and whipped them senseless with switches. The rioters shaved the manes and tails of the lawmen’s horses. They even severed the poor beasts’ ears, then mounted the sheriff and deputy to ride out of Weare down a gauntlet of the aggrieved. Colonial resentment smoldered as the Pine Tree Riot predated the Boston Tea Party by a year and a half.

By 1777, with the colonies in full revolt and the French backing their rebellion, the British needed masts. These strategic components in the hands of the French would be doubly damaging. The intelligence possessing Captain Collier as he advanced up the treacherous Sheepscot was that a suspected mast shipment was making ready north of Wiscasset, bound for Cherbourg.

In the early hours of September 10, Captain Collier ordered the launch of two of the Rainbow’s cutters, the smaller boats for transporting the Royal Marines. He ordered a cutting-out raid on the Gruel, and a hundred marines and sailors set off from Oven’s Mouth under the cover of darkness and rain. Cutting out was the term for commandeering an enemy vessel, in this case, the Gruel. The two cutters snuck past the sleeping village of Wiscasset. Then the raiders rowed north on a flood tide where, according to the impressed fisherman now with the raiders, the Gruel was loading her contraband.

When dawn broke on the Rainbow, Captain Collier saw how close they had come to disaster. The ship could barely swing on her hawser without grounding. Collier launched the remaining cutter, and with deft seamanship, the cutter’s crew wrapped the ship out of its predicament and into the main channel of the Sheepscot. By early afternoon, the Rainbow anchored off Wiscasset Point, positioned to level the town with cannon fire.

Worried locals breathed easier when Captain Collier sent a party ashore under a flag of truce. Collier’s emissary delivered a letter to the local magistrate demanding the surrender of two small cannons and the contraband pines he believed to be loading nearby. Thus, negotiations began with the exchange of letters.

The two cutters arrived at the Gruel near sunrise. The Royal Marines surprised the Gruel’s master, boatswain, and two mates and took them prisoner without a shot or saber slash. After securing the mast-ship, they brought a three-pound cannon aboard and barricaded the boat’s deck with planks already aboard the Gruel. They were ready to return their prize. But they needed a favorable tide, a slack tide just beginning to ebb to clear the shallows and mudflats of the sinuous Sheepscot.

The Gruel’s cook, returning to the boat from shore, saw the capture and ran to tell the local militiamen’s quartermaster. By nine o’clock, the Lincoln County Regiment of Militia, 150 Sons of Liberty, lined the shore and began pelting the raiders with musket and cannon fire. Trapped by the ebbing tide, the raiders were powerless to wrap the Gruel into the river channel. The raiders hunkered down behind their plank armament. Around noon, a second cannon arrived and pulverized the improvised palisade aboard the Gruel. The raiders were in a tough spot.

Captain Collier grew concerned around sunset and launched the remaining cutter. However, the boat returned, fearing an ambush upriver. They were right.

The raiders were running out of options. The Gruel was too large to maneuver down the twisty river. The cutters would have to wrap her off her mooring and tow her to deep water. At ten o’clock, with the moon setting, a raiders’ detachment shoved some of the mast and spars into the river and holed the mast-ship. Then they snuck aboard their cutters in the Gruel’s lee and started downriver. But the Sons of Liberty were waiting. The raiders’ flight stalled when they encountered a boom pulled taunt across the river by the militiamen. The raiders were lucky to hack their way through the heavy rope and out of danger with only one man injured by militia fire. At eleven o’clock, the first cutter hove up along the Rainbow. Captain Collier recovered all the raiders, their prisoners, and both boats by midnight. But the wind was against them as the militia massed at Wiscasset Point.

Negotiations continued while the Rainbow waited for an ebbing flood tide and a favorable wind. Collier bluffed and told the Sons of Liberty they had one hour to evacuate Wiscasset before he opened fire to level the town. It bought him time. Finally, with favorable sailing conditions arriving in the early hours of September 12, Collier relented. He released the prisoners onto a small, commandeered schooner for a promise of safe passage as the Rainbow navigated the Sheepscot narrows.

The Rainbow’s raid on Wiscasset was a measured success. They recovered three main masts and one mizzenmast. The raiders decommissioned the mast-ship and denied the French important contraband. Rainbow suffered only one man wounded. Sir George Collier entered history books as a successful, daring naval officer. He won a major victory against the colonialists in the 1779 Battle of Penobscot Bay.

The fisherman, though, that’s who interests me. Therein lies the lore.

François Arsenault was the fisherman, but he told the British he was Samuel Jones. He was a linguistic chameleon and spoke the English of the colonists, his mother’s tongue. They never suspected he was French. The disdainful British looked down on the colonial dialect and lumped François into the heathen herd.

François was nineteen years old and unmarried. He towered over most other fishermen. His light beard framed his handsome features. He wore rough, sea-worn clothes, and his dark hair flowed from beneath his knit cap pulled low against the Gulf of Maine chill. He was three weeks engaged to Danielle from Monhegan Island.

François was smart. Born and raised on the coast of Maine on the island of Southport, he had learned much in his years fishing with his father. He knew the water, and the vessels that sailed it. But he had never seen a ship the size and menace of the HMS Rainbow. He squinted to make out the detachment of Royal Marines approaching in a cutter. The British were ruthless, and François feared impressment or punishment for disobeying their orders. He thought of Danielle on Monhegan’s Pebble Beach, propped on a worn wool blanket, watching seals cavort on the ledge near shore. Her soft auburn curls danced on her lithe shoulders when she laughed. He would do anything to be with her again.

Six sailors oared the cutter with a coxswain at the stern. It surprised François how fast the boat moved through the chop. Perfectly synced long oars propelled it like a water strider on a pond. Four grim, musket-toting marines stood in the bow of the eight-meter boat, their red coats fluttering in the building nor’easter. Bayonets dangled on their cross belts. François’s single-masted fishing skiff could neither outrun them nor defend against them. He had just set sail for Boothbay when the Rainbow appeared on the horizon.

The British would take no quarter with a Frenchman. So, when the older marine hailed him, he answered in English, “Yes, I fish the Sheepscot. I have fished as far north as the reversing falls above Wiscasset Point.”

The solemn marine declared, “In the name of His Majesty King William III, I order you to come with us. Secure your skiff here and come aboard.”

François hesitated, then waved at the approaching front and pleaded, “But, my lord, my boat may swamp in the coming gale. If I lose my boat, I cannot make a living.”

The pitiless soldier sneered, his words as cold as the murky depths, “If you do not do as I order, you will have no need to make a living.”

A fearful and overwhelmed François played out his anchor, obeyed the order, and began living a lie to save his life.

As a little girl growing up on the coast, she listened to the lore at family gatherings. These get-togethers of thirty or more boisterous relatives always made her smile and laugh. The men built a raging fire in a pit on the rocky shore. Then, in a flame-marred kettle, they boiled lobsters in a stew of salty Atlantic, seaweed, clams, cut potatoes, whole onions, corn on the cob, and hard-boiled eggs. They drank beer and coffee brandy and told stories from the dismal past. They told how François escaped from British servitude, and his subsequent move to Monhegan. Monhegan was French-controlled territory and had been since 1689. With the end of the French–Indian War in 1763, Monhegan became France paisible.

François was with the British when they took the Gruel. He withstood the Sons of Liberty’s bombardment. When the detachment from the Rainbow snuck from the Gruel back to their cutters under fire in the darkness, François parted company in the chaos. On the river’s bank, the militiamen identified him as a friend. Lucky for him. The quartermaster recognized François and vouched for him. Fearing the British might track him and hang him for desertion, François retrieved his skiff and sailed for Monhegan a day later. He and Danielle married on Christmas Eve 1777, and over the next thirty-nine years together, they raised eight healthy, intelligent children with love, hard work, and good fortune. Not a day passed that François did not thank God for allowing him to escape the British and marry Danielle.

Note: It’s well documented that a fisherman was forced into military service by the British in Boothbay Harbor, but what happened next is lost to history. The post-impressment life of François is fiction. In The Tide of Deception, François becomes the familial anchor for my seven-generations-later protagonist, Sandy. Sandy is a single mother of a precocious seventeen-year-old daughter and a senior researcher at Bigelow Laboratory. Sandy is preoccupied with a rogue tide that pounded Boothbay Harbor on October 28, 2008. Her obsession leads her into unforeseen circumstances. And yes, the Boothbay Harbor mystery tide is real.

September 4, 2025

Editorial Response to Washington Post: On WWII anniversary, China seeks to erase U.S. role in victory (September 2, 2025)

Americans played a crucial role in the World War II effort in the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater. China had no indigenous arms capability save clubs and stones. American railway operating battalions, like my father’s unit, the 721st, took charge of the rail link from Calcutta to Ledo, India, and ran freight to an eleven-mile-long depot. From there, U.S. Army Air Corps crews made the unforgiving flight over the Himalayas into China in overfilled C-46s and 47s. All told, 225,000 Americans served in CBI, and the American armed forces employed even more local civilians.

Americans played a crucial role in the World War II effort in the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater. China had no indigenous arms capability save clubs and stones. American railway operating battalions, like my father’s unit, the 721st, took charge of the rail link from Calcutta to Ledo, India, and ran freight to an eleven-mile-long depot. From there, U.S. Army Air Corps crews made the unforgiving flight over the Himalayas into China in overfilled C-46s and 47s. All told, 225,000 Americans served in CBI, and the American armed forces employed even more local civilians.

In 1943, U.S. Army construction units began building and operating the 1,100-mile-long Stilwell Road (also known as the Ledo Road) through the treacherous mountains of Japanese-occupied Burma to Kunming, China, to support Chiang Kai-shek and his warlords in the fight. These 15,000 U.S. Army construction units were African-American enlisted men with white officers, and they died from enemy attacks, disease, and accidents at the rate of a man a mile. When black truck drivers arrived in Kunming, China, in January 1945, Chiang ordered that they switch with white drivers, so as not to upset his racial sensitivities. General Stilwell intervened, pairing white and black drivers.

The Allies saw China as a land-based aircraft carrier from which to bomb the Japanese Home Islands until May of 1945, when the atomic bomb campaign took shape on Tinian. Strategically, the Allies needed China in the war on their side to tie down two million Japanese troops. This was never a foregone alliance with Chiang Kai-shek in charge.

The Allies saw China as a land-based aircraft carrier from which to bomb the Japanese Home Islands until May of 1945, when the atomic bomb campaign took shape on Tinian. Strategically, the Allies needed China in the war on their side to tie down two million Japanese troops. This was never a foregone alliance with Chiang Kai-shek in charge.

China’s contribution to the war was significant, yes, and they lost untold millions to the Japanese. However, the Allies, particularly the Americans and British, bore the heavier burden and made Chinese resistance possible.

Steven James Hantzis, Author

Alexandria, VA

Rails of War: Supplying the Americans and Their Allies in China-Burma-India (University of Nebraska Press, 2017)

University of Manchester (UK)

I was delighted to hear from a professor of history at the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom last week. He wrote:

I read it for the first time about a year ago, and then taught with it last semester in my senior undergrad class on China’s international connections during the second world war. It fills a real gap in the scholarship and my students and I enjoyed both the human stories and the big picture of how CBI was tied together.

Rails of War is a timeless tale of working-class Americans being ordered to undertake a herculean task in a land not of their making and a culture unfamiliar and ageless. They accomplished and exceeded their mission under attack by a merciless enemy, indigenous saboteurs, as well as famine, monsoon, and disease. I’m pleased beyond words that Rails of War resonates today and that the travails of the brave men of the 721st Railway Operating Battalion lives on. Here’s to the University of Manchester. Well done.

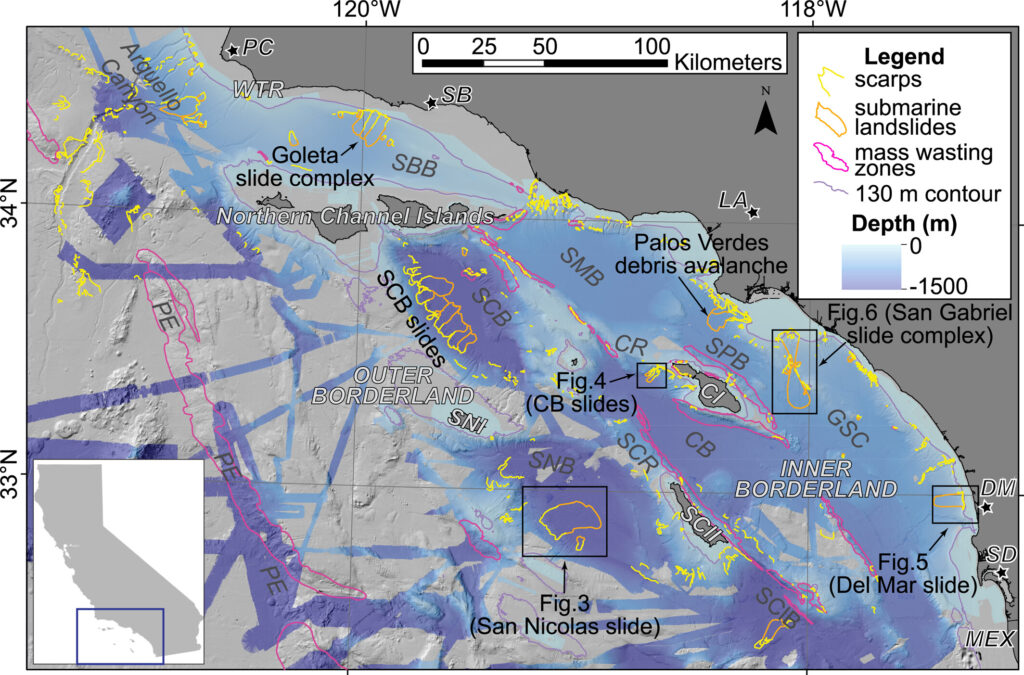

The Tide of Deception readers were one step ahead of the public in understanding the recent 8.8-magnitude earthquake and resulting tsunami on Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula. A close reading of the Washington Post on July 30 found a discussion of submarine landslides as depicted in Deception.

From the Post:

Why one of the world’s biggest earthquakes wasn’t followed by a monster tsunami

Why wave heights were relatively low farther from the quake “is the biggest question at the moment,” said Viacheslav Gusiakov, a tsunami expert in the Siberian branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. As the wave spreads out, it weakens. But the similarly powerful 1952 earthquake in the same region caused bigger waves and more damage in Hawaii than Tuesday’s quake so far.

One possible explanation, Gusiakov said, is a potential absence of a large landslide in the ocean that could have exacerbated the tsunami. Underwater movements of sediments or rocks can add to the energy of a tsunami by up to 90 percent, although this specific case will need to be studied more.

Read The Tide of Deception for a taste of submarine landslides and their continent-changing power.

In new research, scientists from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) have identified nearly 1,500 submarine landslide features off the coast of southern California. These findings highlight significant geological risks to coastal infrastructure and populations, given the potential of submarine landslides to damage seabed cables, moorings, and even trigger tsunamis.

Staff Sergeant James Hantzis, shoved off from Wilmington, California on December 10, 1943, aboard the converted ocean liner, S.S. Mariposa. He and 5,000 GI Railroaders sailed west and south for 15,000 miles en route to India. Few had ever been to sea, let alone this sea.

1 January 1944—S.S. Mariposa, Southwest of Tasmania

The Skuas were grounded, hunger gnawing at them. Birds at the mercy of nature. Like all of God’s beasts, they cack-cack-cacked about the weather unable to do anything about it. They huddled in pairs and the pairs in colonies. Some tended their speckled eggs on the mossy cliffs in their nests of rocks and pebbles, and others stood close for companionship.

Fierce winds blew for two days and even hearty, pesky, pilferers had to put off their raids. This was good news for unborn Adelie penguins still in their eggs, as it was for weak or lame penguins. It was by all counts a good thing for any beast, fish or mammal on the windswept shores of Antarctica clinging to the margins of life.

Vulnerability is opportunity and the voracious Skua seized it, but only when they could fly. If they could fly, their razor-sharp beaks could find the flesh of the weak and convert prey to calories. If they convert the weak to calories, they can breed and fulfill the evolutionary imperative and fill their niche. Why else would any creature be in Antarctica?

The sun would not set on the Skua today, the first day of the New Year 1944. It was austral summer and shoreline temperatures had reached a clement minus twenty-three degrees Fahrenheit. This was as far south as life went on the planet. Beyond these few hundred yards of glacial shoreline, life couldn’t make it. Conditions were harsh and simply too cold.

Some would say the planet itself was alive and celebrating New Year’s Day with relish, roaring with exuberance. Count among those the men on the Mariposa.

The cold of Antarctica is a wind machine. It cools the air above it. The cold air sinks because of its high density and the force of gravity. As the air sinks, it flows across the planet’s southern ice-dome and over the flat frozen plate of the continent, rushing northward unimpeded by topological obstruction. It rushes off the Antarctic shorelines sometimes with the force of a hurricane, a problem for Skuas and seafarers alike. The winds that leave the ice of Antarctica are katabatic or, in Greek katabatos, meaning descending. They are downdrafts that would make an angry Poseidon proud.

Warmer air from the ocean mixes with the frigid katabatic air as it travels northward. This combination creates powerful low-pressure systems spawning polar cyclones that stalk the Southern Ocean, especially in January and February. Long ago, before anyone bothered to write it down, sailors named this part of the world, the ocean below Tasmania and Australia, the Roaring Forties. Forties for the south latitude and roaring for everything else.

Aboard the Mariposa, the railbirds of the 721st also sought cover. Seas broke across her foredeck like water from a fire hose and the only safe place was below. Fierce westerly winds swept the sea before them and the sea was ready to sweep anyone or anything in its way.

Below deck was packed. When the men tried to walk the corridors, it was like an amusement ride, only not amusing. The men who had developed sea legs coped and the men who hadn’t, endured.

The Roaring Forties were the roughest patch of ocean the ship had yet encountered, and the safest place to be was below deck, hunkered. Below, with the men who had stopped using soap. Below, with the reek of disinfectant used to clean up seasickness. Below, with the overtaxed turbines trying to deliver the Mariposa to Bombay and safe harbor. The worst of it lasted five days and when the ship finally escaped into the calmer waters of the South Indian Ocean, everyone onboard breathed a little easier, figuratively and literally. The railbirds returned to their perches on deck, and the jokers in the crowd slowly became more humorous than irritating.

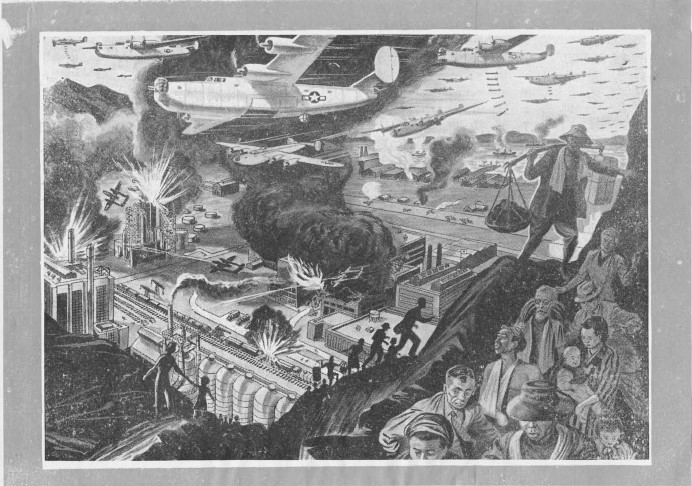

20 May 1945 0733 hours—378 Miles East of Yangkai, China

There is no instance of a country having benefited from prolonged warfare.

Sun Tzu—The Art of War (Circa 475 BCE)[1]

The art of war was an airborne exhibition thanks to General Chennault’s Fourteenth Air Force. In the land of Sun Tzu, two and a half millennia after the noble warrior’s words, the art had changed. It was quite graphic. A product of GI creativity, the new art of war was less contemplative than Sun Tzu’s treatise, but unfailingly communicative.

For instance, the nose art on Colonel Kinnard’s B-25D Mitchell Bomber. It told little about the war, the reasons for it or the tactics involved, but it told something about the warriors who flew her. Under the bomber’s cockpit window, a voluptuous reclining blond in red high heels wore a windblown blue blouse scantly covering her ample bosom. Her puckered lips teased the crew and anyone else looking on with the tagline, Show Me! Clever, since her commander hailed from Missouri. The double entendre was subtle and risqué. A real morale booster. Thus, the art told about the warrior, not much about the war.

However, the small round shoulder patch that each airman aboard the bomber wore was more illustrative. It was a brown derby-crowned bulldog wearing a red and white striped sweater, diving headfirst from the clouds. Fifty-caliber machine guns flared from his nostrils, and he smoked a flaming cannon-cigar. Very Churchillian. This piece of art told you something. It told you about war in China. It was a graphic representation of the task at hand.

The unit’s emblem told you that even though the 491st Bomb Squadron was just that, a bomb squadron, their B-25Ds bristled with strafing weapons. The 491st crew members often went on solo missions instead of flying in large groups and bombing set targets, like in Europe. This was the mission Show Me! had this morning. Sometimes, aircrews received intelligence on their bombing targets and a designated time for the bombs to be dropped. And sometimes, like today, they were told to take off, head in a certain direction and see what they could bomb, shoot or photograph.

The B-25D Mitchell Bomber was a fine airplane, a real workhorse. She was built in a government plant in Kansas City, Kansas, leased to North American Aviation. Nearby, a converted General Motors Fisher Body plant manufactured the outer wings, fuselage side panels, control surfaces, and transparent enclosures.[2] About 4,000 Ds were built during the war, and they saw action in every theater.

The D version carried a crew of six and seven machine guns. She could carry over five thousand pounds of bombs on her wings. She could fly just above the trees and cruise at 233 miles per hour. She was nimble for her size.

Earlier that morning, the crew of Show Me! dropped her bombs on a target of opportunity, a fat Japanese convoy that had stopped to refuel. They were sitting ducks. Now, she was flying low over the green hills and wide rivers east of her base with crew members on the lookout for suitable targets.

They overflew shot-up bridges and houses. Then, as they approached a wide river, the left waist gunner spotted three sampans. The pilot put the plane into a banked left turn and circled the targets. At five hundred yards, the waist gunner fired his twin M-2 Colt-Browning .50-caliber machine gun in short bursts, tat-tat-tat, followed by a couple seconds of silence. Then, tat-tat-tat. In less than one complete circle, the boats splintered and sunk. The largest of the three disintegrated when a secondary explosion of the gasoline drums it had been secreting erupted.

Colonel Kinnard said through the intercom, “Scratch one Japanese oiler. Let’s see what else is on the menu,” and the plane continued eastward, just topping the hills.

A few minutes later, they came upon a small compound of mud houses and the pilot told the nose gunner to fire on approach. The gunner walked the tracers and their dusty footprints through the empty courtyard and into the main building which disappeared in a brown cloud of churning dirt and straw. As the plane passed low overhead, the concussive blast of its twin 1,700 horsepower Wright Cyclones caved in the building’s mud-brick walls. A few soldiers came out of a small building and started shooting at the airplane as it passed by, three hundred yards beyond the target. The tail gunner returned fire, knocking down two and scattering the rest.

Colonel Kinnard informed his crew, “We better go back. Looks like we left a few of ‘em kicking.”

They circled the compound clockwise and the right waist gunner took his toll. Then, with the ground fire suppressed, and the buildings shot to hell, the plane climbed to deliver another item from its art of war catalogue.

Colonel Kinnard keyed the intercom, “Left waist gunner, drop the leaflets and let’s go home.”

The gunner opened the airplane’s escape hatch just ahead of the cylindrical Plexiglas blister housing the port side’s twin machine guns. Then, kneeling next to a stack of twenty bundles, each containing one hundred half-page sized leaflets, he grabbed two. As he threw out the first pair of bundles, a gust caught them and blew them back into the plane’s interior, creating a blizzard of paper. The slipstream was more cooperative with the remaining bundles and soon a graphic, psychological submission graced the countryside.

The top half of each leaflet was a color depiction of an endless wave of approaching war planes trailing bomb sticks all the way to the earth. There were so many planes that they blocked the sun from the sky. At the bottom of the page, Japanese farmers, industrial workers, women, and children fled from burning factories, ports, and bridges. The Japanese characters on the lower half of the leaflet read:

Earthquakes and Tidal Waves can not be Halted

Earthquakes and tidal waves can not be halted. The people realize they are powerless against these overwhelming forces of nature and accept the ruin which follows in their wake.

The military forces of Japan can no longer halt the overwhelming destruction by the United States Air Force than the people can stop an earthquake.

With ever-increasing fury this air force will sweep over Japan like a tidal wave. It will rock the land like an earthquake. With unbelievable striking power, it will bring widespread destruction greater than that caused by all the forces of nature.

The boasting Japanese militarists know they are powerless to stop this terrific devastation. Having totally failed, they now call on helpless old men, women, and children to defend their homes. They are now asking you to assume responsibility for home defense. But what weapons are the military giving you to defend your homes?

Complete destruction can be avoided only by the people over-throwing the militarists and asking for peace. An understanding with the United States means that the peace-loving people of Japan will be saved and will be free to build their country into a modern civilized nation.[3]

After dropping her load of leaflets, bombs and strafing fire, Show Me! Gracefully banked left and headed west towards home. She had once again done her part airing the art of war.

Japan had two million men under arms on the mainland of Asia with the bulk of their forces in China.[4] In the spring of 1945, when they sought to defend the Home Islands and Korea, the troops they needed were on the great land mass to the west. Some say that it was China’s size that ultimately saved her from the Japanese. The American supplies were never enough, the Chinese nationalist fighting forces were subpar, and the communist movement focused on guerilla actions and political organization. No, Japan’s failure to conquer China was classic overreach. The Empire simply bit off more than it could chew. Sun Tzu’s formula for failure, a prolonged war, proved prescriptive.

China started the Second World War as a basket case and ended it the same. The Sino-Japanese war was simply an interruption in a civil war that had started in 1911. Both sides in that war understood that they would fight again as soon as the Japanese left and planned their strategies accordingly.

The Americans used China in a foreign policy relationship based first upon United States’ strategic interests and secondly upon support for democratic reform and economic development. The Americans hoped China would be a counterweight to the rise of Japanese dominance in Asia. The Americans didn’t need to “win the war in China,” although they planned to do so. All they needed was for China to stay in the war and bleed Japan of manpower and resources. This they accomplished.

In 1941, on paper, China had 3.8 million men under arms, the largest army in the world.[5] Forty of her divisions, out of 316, were trained by German and Soviet advisors and mustered with outdated European weapons. The rest were irregular, undermanned and under-equipped. She was a paper tiger. Her soldiers were uneducated, untrained, and sickly. Whatever loyalty they had was to the local warlord that had impressed them into service rather than to Chiang Kai-shek or the nationalist cause. The officers’ corps was equally incompetent with mixed loyalties but, better fed.

As the Japanese reluctantly pushed their campaign beyond Manchuria in 1937, the Soviet Union sent $250 million worth of tanks, trucks, and aircraft to Chiang. The British and French also pitched in. In December 1940, Roosevelt approved $25 million for China to buy one hundred P-40 fighters. Later that spring, he pledged $145 million additional lend-lease equipment. America pledged to outfit thirty infantry divisions and sent the retired air commander, Claire Chennault, to oversee the American Volunteers Group, the Flying Tigers.

Thus began the American commitment to keep China in the war on the side of the Allies. With the loss of Burma and its overland route to China, the American supply effort took to the air. Flying the Hump, over the Himalayas, was a bold operation but it was always limited by the number of aircraft and staging areas. The supplies meant for China often lay piled and stacked in huge depots in Assam, awaiting aircraft and crews to deliver them. So, the Americans built the Ledo Road at the cost of a soldier a mile and focused their attention on northern Burma.

When American lend-lease aid started coming through, Joe Stilwell became the commander in charge and began a tedious and contentious relationship with Chiang. Stilwell had Chaing’s number. The plain-speaking, no-nonsense Stilwell believed that air support was important, but that training and equipping Chinese divisions was the key to success. Working out of U.S. Army Headquarters in Assam, Stilwell kept two Chinese divisions under American command. Chiang, headquartered in Chungking, adopted as the wartime capital after Peking fell, was suspicious and insecure. He worried Stilwell’s divisions might someday constitute another armed movement, a fly in the ointment of his political ambitions.

Chiang never liked the idea of Americans overseeing Chinese troops. So, when that was exactly what Roosevelt proposed in September 1944, that Stilwell take charge of all Chinese ground units, Chiang bucked and threatened to quit the war. Soon thereafter, Stilwell was out and General Wedemeyer was in and Roosevelt split the old CBI command into an India-Burma Theater and a China Theater.

Wedemeyer had a better personal relationship with Chiang than Stilwell, but saw all the same problems. Meanwhile, the Japanese were on the move.

The Doolittle Raid prompted the Japanese to attack Allied airfields in May 1942, even though none of Doolittle’s B-25s landed at Chinese airfields. The Japanese Army in China, the Chinese Expeditionary Force, pushed west, but their drive stalled before they could destroy the network of American airfields. A few months later, the Japanese began worrying about the potent B-29s in China because of their range and threat to the Home Islands. In April 1944, they launched Operation Ichigo.

The Japanese promptly began pushing the Chinese out of their way. Chiang’s forces were completely ineffective and had it not been for American airpower attacking Japanese supply lines and troop concentrations, even more would have been lost.

By the end of 1944, as things were looking up in Burma, the picture was far less promising in China. The Japanese were still advancing at will. Operation Ichigo had succeeded. The Japanese had captured Kweilin and then Liuchow, an important Fourteenth Air Force base. They had linked their northern and southern armies and secured a rail link to Indochina.

In January 1945, Chinese defenses were weak. The Allies redeployed the old Stilwell divisions and moved the American Mars Taskforce from Burma to China to stiffen the resistance. This, of course, put the burden of winning Burma completely on the shoulders of General Slim and his British units.

With the completion of the Ledo Road and subsequent reopening of the Burma Road in February 1945, the supply picture in China improved. About that time, General Wedemeyer began making limited progress organizing Alpha Force, thirty American-trained and equipped Chinese divisions.

On April 8, 1945, Japan launched an offensive to capture the American base at Chihchiang, the Allied strongpoint guarding the approaches to Kunming. This was the supply center for all of China, and Chungking, the capital. Chiang’s army again melted in the heat of battle. But this time, riding to the rescue, the Americans hurriedly transported their new 6th and 94th Armies to Chihchiang. By June 7, they pushed the Japanese back to their original points of attack.[6] It was the last major Japanese offensive in China.

On April 1, 1945, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters promulgated Plan Ketsu, a reorganization of their entire ground deployment. The move would strengthen their defensive positions for the Home Islands and fend off an Allied landing in southern China. Ketsu ordered the return of thousands of soldiers to Japan and the concentration of China Expeditionary Forces along the coast.

So, as the Japanese slowly pulled out of territory they had gained during Ichigo, the Chinese cautiously moved in to fill the void. Thus, the “Battle for China” was won, not so much by the Chinese but by the Americans and British who were making steady progress throughout the Pacific and Burma. The Japanese were also worried by the looming threat that the Soviets might soon join the fight.

It was wise for the Japanese to worry. About this time, mid-May 1945, President Truman authorized Operation Downfall, the invasion of Japan. The first part of the plan, Operation Olympic, was set for November 1, 1945. Operation Coronet would follow in March 1946.

Olympic would put an invasion force ashore on the southern-most Home Island of Kyushu, the same island that Kublai Khan tried to take in 1274. Four months later, Coronet would land another force on Honshu south of Tokyo. The casualties, as estimated by General Curtis Lemay, would be “well up into the imaginative brackets and then some.”[7] The United States Government, in prudent preparation, ordered the minting of half a million Purple Hearts.

-SJH Copyright 2023

[1] “Sunzi.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 4 Dec. 2006

http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9070336. The passage is from Chapter II, Waging War, item 6.

[2] “North American B-25D Mitchell” North American B-25D Mitchell Retrieved June 16, 2008 Online: http://home.att.net/~jbaugher2/b25_7.html.

[3] “Aerial Propaganda Leaflet Database Second World War” Psywar.org Retrieved June 16, 2008 Online: http://www.psywar.org/apddetailsdb.php?detail=1945PAC151J1.

[4] Mark D. Sherry. China Offensive 5 May-2 September 1945 (U.S. Army Center of Military History, U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 1).

[5] Mark D. Sherry. China Defensive (U.S. Army Center of Military History, U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 5).

[6] Mark D. Sherry. China Offensive 5 May-2 September 1945 (U.S. Army Center of Military History, U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 24).

[7] D. M. Giangreco. Casualty Projections for The U.S. Invasions Of Japan, 1945-1946: Planning and Policy Implications (The Journal of Military History, 61, July 1997, p. 521-82). Also at http://home.kc.rr.com/casualties/.