The Art of War

20 May 1945 0733 hours—378 Miles East of Yangkai, China

There is no instance of a country having benefited from prolonged warfare.

Sun Tzu—The Art of War (Circa 475 BCE)[1]

The art of war was an airborne exhibition thanks to General Chennault’s Fourteenth Air Force. In the land of Sun Tzu, two and a half millennia after the noble warrior’s words, the art had changed. It was quite graphic. A product of GI creativity, the new art of war was less contemplative than Sun Tzu’s treatise, but unfailingly communicative.

For instance, the nose art on Colonel Kinnard’s B-25D Mitchell Bomber. It told little about the war, the reasons for it or the tactics involved, but it told something about the warriors who flew her. Under the bomber’s cockpit window, a voluptuous reclining blond in red high heels wore a windblown blue blouse scantly covering her ample bosom. Her puckered lips teased the crew and anyone else looking on with the tagline, Show Me! Clever, since her commander hailed from Missouri. The double entendre was subtle and risqué. A real morale booster. Thus, the art told about the warrior, not much about the war.

However, the small round shoulder patch that each airman aboard the bomber wore was more illustrative. It was a brown derby-crowned bulldog wearing a red and white striped sweater, diving headfirst from the clouds. Fifty-caliber machine guns flared from his nostrils, and he smoked a flaming cannon-cigar. Very Churchillian. This piece of art told you something. It told you about war in China. It was a graphic representation of the task at hand.

The unit’s emblem told you that even though the 491st Bomb Squadron was just that, a bomb squadron, their B-25Ds bristled with strafing weapons. The 491st crew members often went on solo missions instead of flying in large groups and bombing set targets, like in Europe. This was the mission Show Me! had this morning. Sometimes, aircrews received intelligence on their bombing targets and a designated time for the bombs to be dropped. And sometimes, like today, they were told to take off, head in a certain direction and see what they could bomb, shoot or photograph.

The B-25D Mitchell Bomber was a fine airplane, a real workhorse. She was built in a government plant in Kansas City, Kansas, leased to North American Aviation. Nearby, a converted General Motors Fisher Body plant manufactured the outer wings, fuselage side panels, control surfaces, and transparent enclosures.[2] About 4,000 Ds were built during the war, and they saw action in every theater.

The D version carried a crew of six and seven machine guns. She could carry over five thousand pounds of bombs on her wings. She could fly just above the trees and cruise at 233 miles per hour. She was nimble for her size.

Earlier that morning, the crew of Show Me! dropped her bombs on a target of opportunity, a fat Japanese convoy that had stopped to refuel. They were sitting ducks. Now, she was flying low over the green hills and wide rivers east of her base with crew members on the lookout for suitable targets.

They overflew shot-up bridges and houses. Then, as they approached a wide river, the left waist gunner spotted three sampans. The pilot put the plane into a banked left turn and circled the targets. At five hundred yards, the waist gunner fired his twin M-2 Colt-Browning .50-caliber machine gun in short bursts, tat-tat-tat, followed by a couple seconds of silence. Then, tat-tat-tat. In less than one complete circle, the boats splintered and sunk. The largest of the three disintegrated when a secondary explosion of the gasoline drums it had been secreting erupted.

Colonel Kinnard said through the intercom, “Scratch one Japanese oiler. Let’s see what else is on the menu,” and the plane continued eastward, just topping the hills.

A few minutes later, they came upon a small compound of mud houses and the pilot told the nose gunner to fire on approach. The gunner walked the tracers and their dusty footprints through the empty courtyard and into the main building which disappeared in a brown cloud of churning dirt and straw. As the plane passed low overhead, the concussive blast of its twin 1,700 horsepower Wright Cyclones caved in the building’s mud-brick walls. A few soldiers came out of a small building and started shooting at the airplane as it passed by, three hundred yards beyond the target. The tail gunner returned fire, knocking down two and scattering the rest.

Colonel Kinnard informed his crew, “We better go back. Looks like we left a few of ‘em kicking.”

They circled the compound clockwise and the right waist gunner took his toll. Then, with the ground fire suppressed, and the buildings shot to hell, the plane climbed to deliver another item from its art of war catalogue.

Colonel Kinnard keyed the intercom, “Left waist gunner, drop the leaflets and let’s go home.”

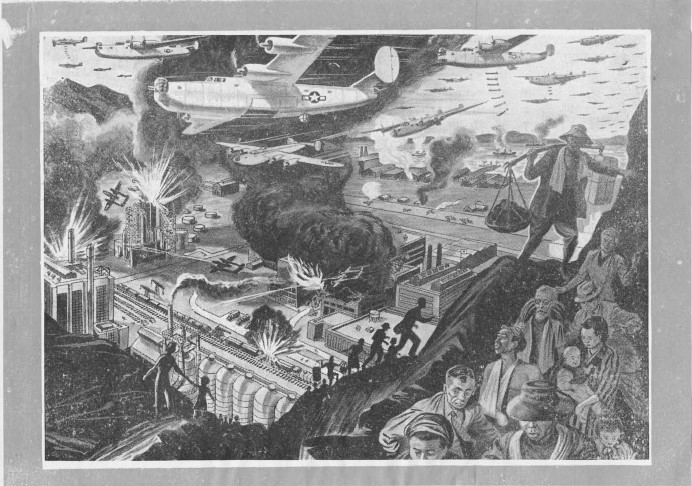

The gunner opened the airplane’s escape hatch just ahead of the cylindrical Plexiglas blister housing the port side’s twin machine guns. Then, kneeling next to a stack of twenty bundles, each containing one hundred half-page sized leaflets, he grabbed two. As he threw out the first pair of bundles, a gust caught them and blew them back into the plane’s interior, creating a blizzard of paper. The slipstream was more cooperative with the remaining bundles and soon a graphic, psychological submission graced the countryside.

The top half of each leaflet was a color depiction of an endless wave of approaching war planes trailing bomb sticks all the way to the earth. There were so many planes that they blocked the sun from the sky. At the bottom of the page, Japanese farmers, industrial workers, women, and children fled from burning factories, ports, and bridges. The Japanese characters on the lower half of the leaflet read:

Earthquakes and Tidal Waves can not be Halted

Earthquakes and tidal waves can not be halted. The people realize they are powerless against these overwhelming forces of nature and accept the ruin which follows in their wake.

The military forces of Japan can no longer halt the overwhelming destruction by the United States Air Force than the people can stop an earthquake.

With ever-increasing fury this air force will sweep over Japan like a tidal wave. It will rock the land like an earthquake. With unbelievable striking power, it will bring widespread destruction greater than that caused by all the forces of nature.

The boasting Japanese militarists know they are powerless to stop this terrific devastation. Having totally failed, they now call on helpless old men, women, and children to defend their homes. They are now asking you to assume responsibility for home defense. But what weapons are the military giving you to defend your homes?

Complete destruction can be avoided only by the people over-throwing the militarists and asking for peace. An understanding with the United States means that the peace-loving people of Japan will be saved and will be free to build their country into a modern civilized nation.[3]

After dropping her load of leaflets, bombs and strafing fire, Show Me! Gracefully banked left and headed west towards home. She had once again done her part airing the art of war.

Japan had two million men under arms on the mainland of Asia with the bulk of their forces in China.[4] In the spring of 1945, when they sought to defend the Home Islands and Korea, the troops they needed were on the great land mass to the west. Some say that it was China’s size that ultimately saved her from the Japanese. The American supplies were never enough, the Chinese nationalist fighting forces were subpar, and the communist movement focused on guerilla actions and political organization. No, Japan’s failure to conquer China was classic overreach. The Empire simply bit off more than it could chew. Sun Tzu’s formula for failure, a prolonged war, proved prescriptive.

China started the Second World War as a basket case and ended it the same. The Sino-Japanese war was simply an interruption in a civil war that had started in 1911. Both sides in that war understood that they would fight again as soon as the Japanese left and planned their strategies accordingly.

The Americans used China in a foreign policy relationship based first upon United States’ strategic interests and secondly upon support for democratic reform and economic development. The Americans hoped China would be a counterweight to the rise of Japanese dominance in Asia. The Americans didn’t need to “win the war in China,” although they planned to do so. All they needed was for China to stay in the war and bleed Japan of manpower and resources. This they accomplished.

In 1941, on paper, China had 3.8 million men under arms, the largest army in the world.[5] Forty of her divisions, out of 316, were trained by German and Soviet advisors and mustered with outdated European weapons. The rest were irregular, undermanned and under-equipped. She was a paper tiger. Her soldiers were uneducated, untrained, and sickly. Whatever loyalty they had was to the local warlord that had impressed them into service rather than to Chiang Kai-shek or the nationalist cause. The officers’ corps was equally incompetent with mixed loyalties but, better fed.

As the Japanese reluctantly pushed their campaign beyond Manchuria in 1937, the Soviet Union sent $250 million worth of tanks, trucks, and aircraft to Chiang. The British and French also pitched in. In December 1940, Roosevelt approved $25 million for China to buy one hundred P-40 fighters. Later that spring, he pledged $145 million additional lend-lease equipment. America pledged to outfit thirty infantry divisions and sent the retired air commander, Claire Chennault, to oversee the American Volunteers Group, the Flying Tigers.

Thus began the American commitment to keep China in the war on the side of the Allies. With the loss of Burma and its overland route to China, the American supply effort took to the air. Flying the Hump, over the Himalayas, was a bold operation but it was always limited by the number of aircraft and staging areas. The supplies meant for China often lay piled and stacked in huge depots in Assam, awaiting aircraft and crews to deliver them. So, the Americans built the Ledo Road at the cost of a soldier a mile and focused their attention on northern Burma.

When American lend-lease aid started coming through, Joe Stilwell became the commander in charge and began a tedious and contentious relationship with Chiang. Stilwell had Chaing’s number. The plain-speaking, no-nonsense Stilwell believed that air support was important, but that training and equipping Chinese divisions was the key to success. Working out of U.S. Army Headquarters in Assam, Stilwell kept two Chinese divisions under American command. Chiang, headquartered in Chungking, adopted as the wartime capital after Peking fell, was suspicious and insecure. He worried Stilwell’s divisions might someday constitute another armed movement, a fly in the ointment of his political ambitions.

Chiang never liked the idea of Americans overseeing Chinese troops. So, when that was exactly what Roosevelt proposed in September 1944, that Stilwell take charge of all Chinese ground units, Chiang bucked and threatened to quit the war. Soon thereafter, Stilwell was out and General Wedemeyer was in and Roosevelt split the old CBI command into an India-Burma Theater and a China Theater.

Wedemeyer had a better personal relationship with Chiang than Stilwell, but saw all the same problems. Meanwhile, the Japanese were on the move.

The Doolittle Raid prompted the Japanese to attack Allied airfields in May 1942, even though none of Doolittle’s B-25s landed at Chinese airfields. The Japanese Army in China, the Chinese Expeditionary Force, pushed west, but their drive stalled before they could destroy the network of American airfields. A few months later, the Japanese began worrying about the potent B-29s in China because of their range and threat to the Home Islands. In April 1944, they launched Operation Ichigo.

The Japanese promptly began pushing the Chinese out of their way. Chiang’s forces were completely ineffective and had it not been for American airpower attacking Japanese supply lines and troop concentrations, even more would have been lost.

By the end of 1944, as things were looking up in Burma, the picture was far less promising in China. The Japanese were still advancing at will. Operation Ichigo had succeeded. The Japanese had captured Kweilin and then Liuchow, an important Fourteenth Air Force base. They had linked their northern and southern armies and secured a rail link to Indochina.

In January 1945, Chinese defenses were weak. The Allies redeployed the old Stilwell divisions and moved the American Mars Taskforce from Burma to China to stiffen the resistance. This, of course, put the burden of winning Burma completely on the shoulders of General Slim and his British units.

With the completion of the Ledo Road and subsequent reopening of the Burma Road in February 1945, the supply picture in China improved. About that time, General Wedemeyer began making limited progress organizing Alpha Force, thirty American-trained and equipped Chinese divisions.

On April 8, 1945, Japan launched an offensive to capture the American base at Chihchiang, the Allied strongpoint guarding the approaches to Kunming. This was the supply center for all of China, and Chungking, the capital. Chiang’s army again melted in the heat of battle. But this time, riding to the rescue, the Americans hurriedly transported their new 6th and 94th Armies to Chihchiang. By June 7, they pushed the Japanese back to their original points of attack.[6] It was the last major Japanese offensive in China.

On April 1, 1945, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters promulgated Plan Ketsu, a reorganization of their entire ground deployment. The move would strengthen their defensive positions for the Home Islands and fend off an Allied landing in southern China. Ketsu ordered the return of thousands of soldiers to Japan and the concentration of China Expeditionary Forces along the coast.

So, as the Japanese slowly pulled out of territory they had gained during Ichigo, the Chinese cautiously moved in to fill the void. Thus, the “Battle for China” was won, not so much by the Chinese but by the Americans and British who were making steady progress throughout the Pacific and Burma. The Japanese were also worried by the looming threat that the Soviets might soon join the fight.

It was wise for the Japanese to worry. About this time, mid-May 1945, President Truman authorized Operation Downfall, the invasion of Japan. The first part of the plan, Operation Olympic, was set for November 1, 1945. Operation Coronet would follow in March 1946.

Olympic would put an invasion force ashore on the southern-most Home Island of Kyushu, the same island that Kublai Khan tried to take in 1274. Four months later, Coronet would land another force on Honshu south of Tokyo. The casualties, as estimated by General Curtis Lemay, would be “well up into the imaginative brackets and then some.”[7] The United States Government, in prudent preparation, ordered the minting of half a million Purple Hearts.

-SJH Copyright 2023

[1] “Sunzi.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 4 Dec. 2006

http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9070336. The passage is from Chapter II, Waging War, item 6.

[2] “North American B-25D Mitchell” North American B-25D Mitchell Retrieved June 16, 2008 Online: http://home.att.net/~jbaugher2/b25_7.html.

[3] “Aerial Propaganda Leaflet Database Second World War” Psywar.org Retrieved June 16, 2008 Online: http://www.psywar.org/apddetailsdb.php?detail=1945PAC151J1.

[4] Mark D. Sherry. China Offensive 5 May-2 September 1945 (U.S. Army Center of Military History, U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 1).

[5] Mark D. Sherry. China Defensive (U.S. Army Center of Military History, U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 5).

[6] Mark D. Sherry. China Offensive 5 May-2 September 1945 (U.S. Army Center of Military History, U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 24).

[7] D. M. Giangreco. Casualty Projections for The U.S. Invasions Of Japan, 1945-1946: Planning and Policy Implications (The Journal of Military History, 61, July 1997, p. 521-82). Also at http://home.kc.rr.com/casualties/.