From Where They Came

From Where They Came

This Memorial Day allow me to introduce a few of the men who led by example and molded America’s modern Special Operations Force. They were British, part of a secret organization called the Special Operations Executive (SOE). During World War II, SOE commandos fought in every theater and found time to come to America and train groups within the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the CIA. OSS commando units were called Operational Groups or OGs. The men in OGs were highly vetted, physically honed, and fluent in at least one foreign language. They weren’t spies; they fought behind enemy lines in American uniforms. Typically recruited from the U.S. Army and Marines, they were Norwegians, French, Italians, Austrians, Germans, Dutch, Hungarians, Spaniards, Poles, Czechs-Slovaks, Yugoslavs, Chinese, Korean, and Thai. And they were Greeks.

The manuscript I’m working on is American Andarte. Andarte is Greek for resistance fighter or guerilla. Greece was full of them during the Italian, Bulgarian, and German occupation of World War II. Most andartes belonged to either EDES or EAM-ELAS, rival resistance organizations within Greece. EAM-ELAS was larger and incorporated Greek communists, other progressives, and anti-monarchists. EDES was conservative and supported the king and accommodated the Germans. Believe me, Greek politics during World War II was complex. The book will supply details.

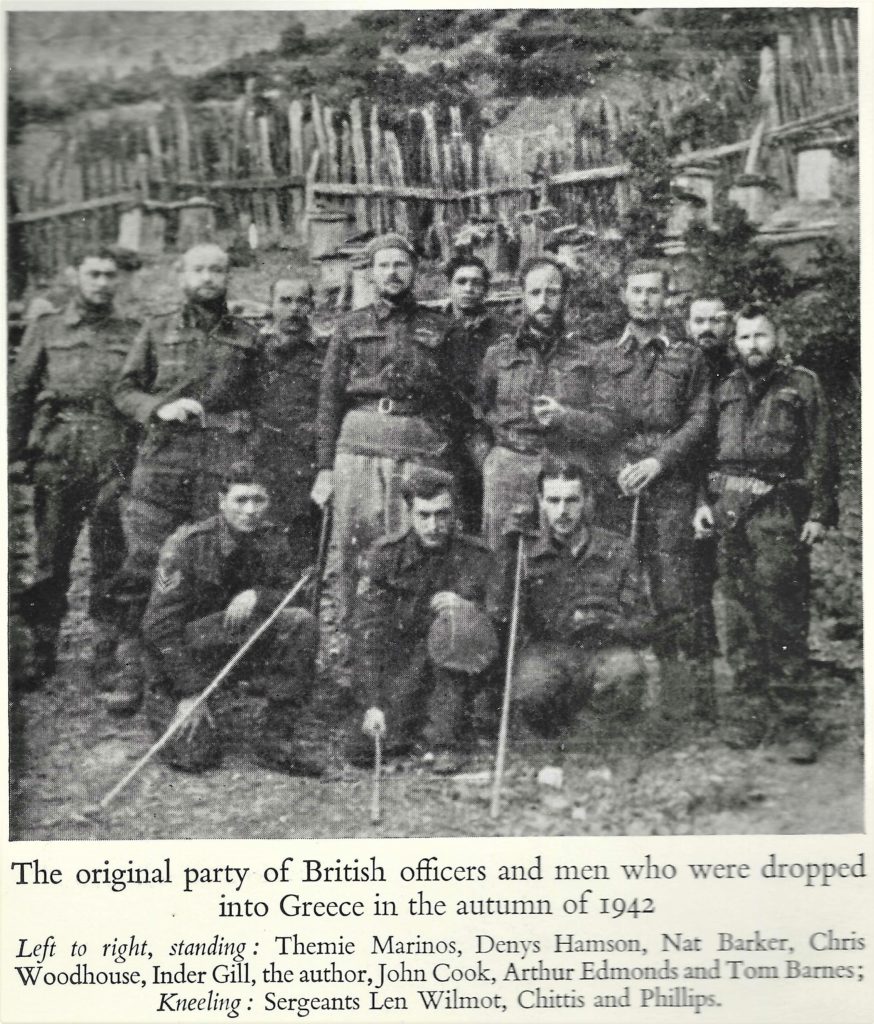

This vignette picks up in September 1942 with the first British SOE mission to Greece. The American OSS OGs would arrive a year and a half later in April 1944. Theirs is a fascinating story, classified until 1987. Until then, the CIA prohibited these American combat veterans from talking about their service. One hundred and eighty-one American OSS commandos served in Greece.

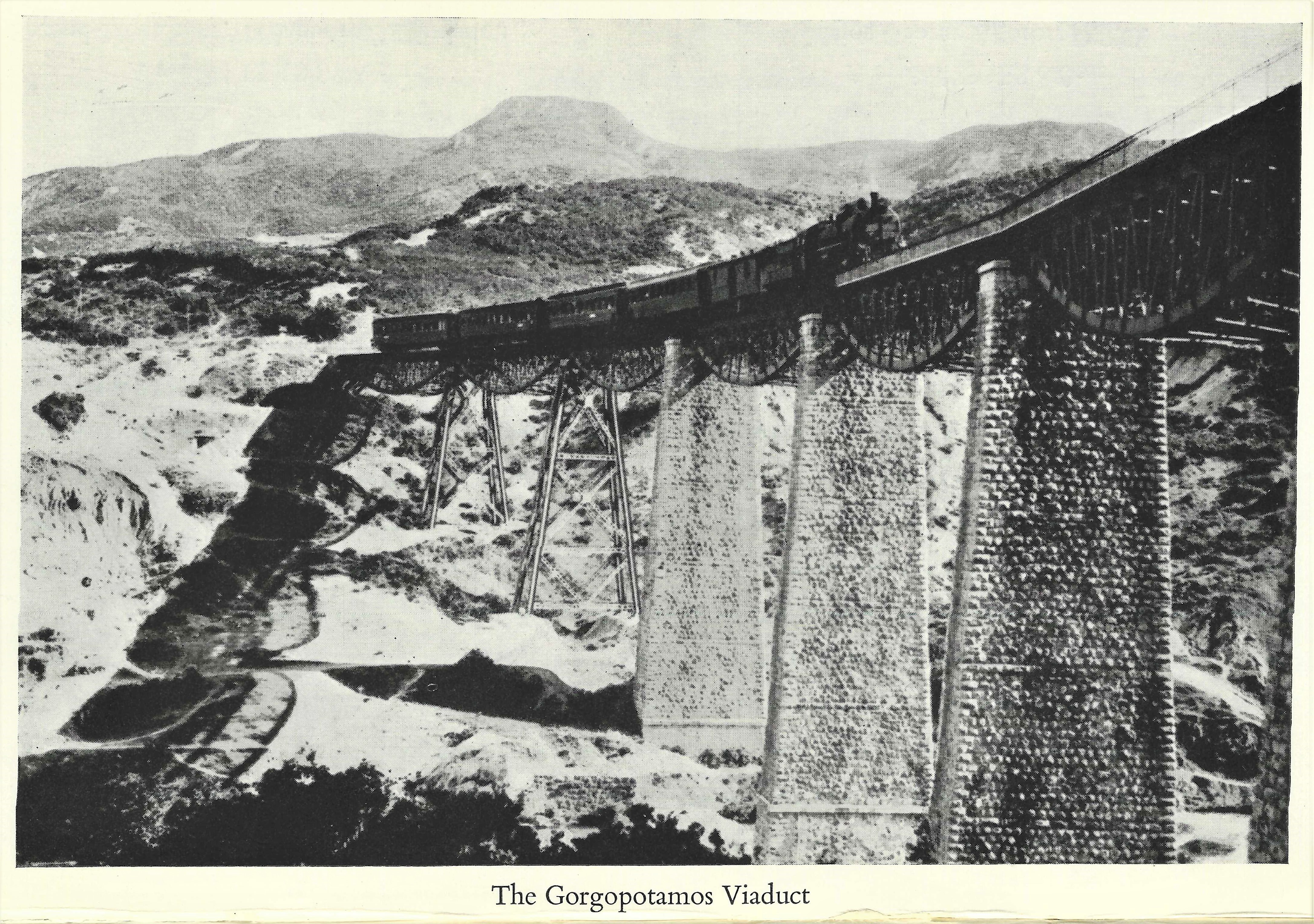

This is a section from a chapter in my manuscript so context might be foggy. The focus is on the British SOE and their first contact in Greece. The viaduct in this vignette is the Gorgopotamos Railroad Bridge. The sabotage of this crucial transportation link with the help of Greek andartes was their first SOE action. (There’s a great video about the mission featuring Monty Woodhouse.)

A few months later, the SOE struck again, this time alone. They brought down the highest railroad bridge in the country, the Asopos Viaduct, in an action believed impossible. Asopos is an entirely unique story covered in the manuscript and not for this post. It is enough to say that when the spans of Asopos Viaduct fell into the rushing river 330 feet below; the SOE made their mark on the history of warfare. The United States Army Special Operations Command today says that the attack on the Asopos Viaduct “was probably the single most spectacular exploit of its kind in World War II.” The Germans were so certain that the destruction of the Asopos Viaduct could only be an act of treachery that they shot the entire garrison guarding it that night.

Cairo, Egypt—September 1942

For all the complexity and drama that was Greek resistance politics, the Greek railway network was easy to understand. There was one standard-gauge mainline. It ran from the Port of Piraeus through Athens to Salonika in Greece, and from there to Sofia, Bulgaria, then Nis and Belgrade and Zagreb in Yugoslavia. At Zagreb, lines fanned out to Austria, Italy, and Hungary. The rail line carried forty-eight trains a day and completed an essential military line of communication. It stretched from the industrial centers of Germany through Piraeus to the Libyan ports of Tobruk and Benghazi. The Greek railroad was the only supply route with the ability to carry the weight of war. Over it rolled troops and supplies for occupation of the Balkans and the resupply of Rommel’s North Afrika Korps. It was a strategic target, of which the British took immediate notice. In the fall of 1942, they handed the problem to the Special Operations Executive (SOE), informally known as “The Baker Street Irregulars” or “Churchill’s Secret Army.”

On September 30, 1942, under a waning gibbous moon offering a bit too much light for the stealth intended, Lt. Colonel Eddie Myers, made a last check of men and supplies. Myers was a scrappy, assertive, thirty-six-year-old sapper from Kensington by way of the Middle East. The commander of the British SOE team climbed into an American-crewed B-24 Liberator on the tarmac of Deversoir Aerodrome. Deversoir was on the northern shore of Great Bitter Lake at the entrance of the Suez Canal.

Myers and three other SOE commandos boarded the first plane, and two more groups of four boarded two other planes. Each man, dressed in a British military uniform, carried an Enfield No. 2 Mk I .38 caliber revolver and a Fairbairn-Sykes commando dagger. They packed field dressings, and a Baker Street Kit comprising a compass that looked like a button, a map disguised as a silk scarf, a leather belt secreting two gold sovereigns, rations, torches, and poison pills for use if captured. They were parachuting into Greece. Their Sten submachine guns, grenades, and the detonators for their plastic explosives dropped separately in metal pod canisters.

They had done this before, two nights before. After flying four hours, eight hundred miles, over the Mediterranean into the mountains of Roumeli, Central Greece, they had turned away for Cairo. They had failed to spot the expected signal fires positioned to look like a cross. Tonight, was better. The pilot keyed the intercom and told Myers he thought he saw three fires burning in a valley below.

The snow on Mount Giona reflected the light of the moon and cast the palest glow on an alien world. The ancient name for Mount Giona is Aselinon Oros or moonless mountain. But tonight, the name misled. The Liberator descended to just above the peaks as Myers opened the bottom hatch in the airplane’s bay and jumped into the frigid darkness of the barely luminous unknown.

He fought updrafts from the mountain peaks. Buoyed and buffeted he blew away from his intended valley and drifted toward a forest of fir trees. He fought his heavy pack but couldn’t correct his descent. He landed high in a tall fir and crashed through its branches, ending on the ground with his parachute tangled above. His pack ripped from him in the fall, snagged on a stout limb and swung above. When he hit the ground, he sat for a few minutes in the snow and fir needles gathering his wits. The throbbing pulse of twelve, 14-cylinder Pratt & Whitney engines faded into the void. The Liberators were going home. It became silent, and Myers was alone.

There was no sign of the equipment pods or other commandos. Myers stood on the steep mountain slope, barely able to move without tumbling forward, and tried to stay calm. First, he lit a flare, and that drew no attention. Then he lit a bonfire which gave the same result. He stumbled towards the valley using trees as braking points for his descent. There in the valley, he met two Greek shepherds. Myers did not speak Greek, but the three pantomimed and worked out that they would stay put until dawn.

As the sun came up, Myers returned to the tree where he landed surprised that his parachute and pack were missing. That was when Tom Barnes, a New Zealander and one of Myer’s team, walked through the trees to Myers and the shepherds. He was unhurt. Barnes had received a signal from a third commando, Len Wilmot, and the two commandos went looking for him. The two shepherds went looking for the fourth commando, Denys Hamson, the only Greek-speaker in their group.

When the commandos and shepherds met at midday, the shepherds had found Hamson, and Wilmot appeared soon after. The team, one of three, was back together, intact, and Operation Harling was underway.

The second team, headed by Christopher Woodhouse, fared better. They landed seventeen kilometers north of Myers on the other side of Mount Giona. The four commandos landed without separation or injury. Soon Woodhouse’s team met, unexpectedly, armed men. The tension lifted when the andartes decided they were British and not German. The leader was a Greek who said he was expecting an explosive supply drop to blow up the retaining walls of the Corinth Canal. With him were two Cypriots, escaped prisoners of war.

The andartes led them to a village. There, Woodhouse, who went by Monty instead of Lord Terrington of Huddersfield, welcomed their equipment canisters retrieved by the villagers. But he watched in horror as children munched on the plastic explosive bars thinking they were fudge. They got sick but survived. Woodhouse, an Oxford-educated classics scholar and a fluent speaker of Greek, came first to understand the strangeness of occupied Greece, a country of scant resemblance to the land of Pericles.

Following the advice of a supportive villager the Woodhouse team moved to a cave on the eastern slopes of Mount Giona on a plateau called Prophet Elias. The cave was big enough to shelter all three commando groups. It was a three-day hike across a vast and rugged terrain. They trudged through deep snow in the valleys while the wind blew in gales cutting like the icy steel of a knife. Woodhouse welcomed Myers and his team and the two shepherds into their grotto sanctuary two days after arrival.

They knew the Italians were searching for them. The Italians had heard the Liberators on two nights. The SOE men moved to another cave that offered a better defense and tried to contact the third team.

The third team did not jump with the other two on September 30. They couldn’t spot signal fires and returned to Cairo. Three weeks later, they jumped blind and misjudged their location, dropping into the Karpenisi Valley near a large Italian garrison. Aris Velouchiotis commanded an EAM-ELAS unit that rescued the SOE team from certain capture. It took the three SOE teams a month to reunite.

Meanwhile, Woodhouse and Myers met the local EDES leader, Zervas, a short and rotund man of a carefree persona underlying his reputation as a brigand. Zervas controlled one hundred fighters. Later, they met Aris, the EAM-ELAS commander. He was thin, lanky, and hard-eyed, always alert and examining his surroundings. Aris commanded a larger, more disciplined force. His andartes controlled the territory on which rose the primary target of Operation Harling, the Gorgopotamos Bridge. But, before they could destroy one bridge, Myers had to build another.

To say EAM-ELAS and EDES were bitter rivals was to sugarcoat the reality. Both groups would not hesitate to attack and kill the other, given a provocation or a chance. Their politics clashed, and their leaders clashed. EAM-ELAS was the better organized and disciplined and larger. But British strategists fearing communist influence favored EDES. Myers and Woodhouse were to walk a diplomatic tightwire and forge a truce to carry out Operation Harling.

When they met with Aris of EAM-ELAS and Zervas of EDES, brandy helped to relax the grim Aris, and the carrot of arms and ammunition, and air support and resupply sweetened the proposition. Aris was less enthusiastic about the attack than Zervas. The EAM-ELAS top leadership believed that countryside military raids were less productive than urban actions. Aris was under orders “not to attack formed bodies of the enemy.”

Aris bucked EAM-ELAS leadership and agreed to take part. With the shaking of hands all around and toasts to the pact, EAM-ELAS and EDES pledged to work together for the attack on the Gorgopotamos Bridge. The British saw this arrangement as perhaps the start of a lasting reconciliation and a budding alliance between the organizations. But in Greece, the old is never far from the present.

Operation Animals set for June 21, 1943, called for an ambitious campaign of sabotage in Greece. SOE attacks with andarte support were to fool the Axis Powers into believing that Greece was the target of an Allied amphibious landing, instead of Sicily. Operation Animals was part of a broader campaign, Operation Barclay. This plan involved twelve fake Allied divisions, bogus troop movements, and corresponding fake radio communications. The deception was to fool the Germans into reinforcing Greece and forget about Sicily. Operation Mincemeat, the dead body, brought ashore in Spain, was part of Operation Barclay.

The British SOE commandos parachuted into Greece with three targets, bridges across the Papadia, Asopos, and Gorgopotamos rivers, all Roumeli railroad viaducts. Colonel Myers, while waiting to reunite with Woodhouse, reconnoitered all three and found Gorgopotamos Bridge the best choice.

Constructed in 1905 and considered an engineering marvel, the Gorgopotamos Bridge is ninety-five miles northwest of Athens. The bridge rises 112 feet to span the gorge and churning river for seven hundred feet. Gorgopotamos means the rushing river in Greek. Over it crossed a single line of railway, the lifeblood of Germany’s campaigns in the Balkans and North Africa.

As Myers crawled to his vantage at dawn, he could see through powerful binoculars the seven sub-linear spans supported by six pylons of the massive Gorgopotamos structure. The four central pylons were stone and would be impervious to the plastic explosives of the SOE. But iron piers, girders, and trusses supported either end. These would be the target for the four hundred pounds of shaped charges on the night of November 25, 1942.

One hundred Italians and five Germans guarded the bridge with pillboxes and heavy machineguns at either approach. With the SOE team of 12 and 86 fighters from EAM-ELAS and 52 from EDES, the attack would go forward with 150 fighters. The plan was simple, but the execution was treacherous.

Before 1100 hours, small groups of andartes went up the rail line both north and south to cut communications wires, halt advancing trains, and block any attempt at reinforcement. Then, at 1114 hours, all hell broke loose as the andartes attacked pillboxes at either end of the bridge. The southern position fell first with the Italians running to escape the attack. The northern defense fell when Myers sent his small contingent of reinforcements. As the attackers gained control of the bridge, the explosives team and eight mules made their way down the rough brush and slippery stones of the gorge. At the floor of the gorge, they waded into the powerful, unsettled currents of the river, and across a narrow plank bridge.

At the base of the bridge, the explosives team shaped and reshaped their charges and attached them to the girders. At 0130 hours on the morning of the 26th, the first explosion collapsed the two spans at either end of the bridge. The severed sections fell into the gorge with a crash to the cheers of fighters. An hour later, with explosives left over, the SOE sappers demolished the fallen spans where they landed. With the sky lightening at the hint of dawn, a green Very light spread an eerie glow on the gray-rose palate and signaled the retreat. The attackers withdrew at 0430 hours for a fifteen-hour trek to their hideout. The andartes suffered only four casualties and no killed-in-action. The SOE men were untouched and Myers estimated the Italian dead at thirty.

At the hideout, Myers expressed his gratitude to both Zervas and Aris. He told them the attack could not have been successful without them. Myers sent a messenger to Athens to arrange a supply drop of boots, clothing, arms, and whiskey for EDES and Zervas. Aris requested the same for EAM-ELAS, but Myers had no authority for the communist request. He instead gave Aris and EAM-ELAS 250 gold sovereigns. Myers told Zervas and Aris that he had recommended them for decorations and commended them for their service to the Allied cause. Zervas was grateful but Aris wanted none of it and told Myers he preferred boots for his fighters.

The German repair of the Gorgopotamos Bridge took six weeks, denying Rommel’s Afrika Korps two thousand trainloads of supplies. The repair to German respect for Italian courage under fire never happened. The Germans took over security for the entire railway system, straining their forces in Greece and the Balkans. Less than a month later, the 11th Luftwaffe Field Division moved into Attica north of Athens.

On December 1, 1942, ten villagers from tiny Ypati, hands bound, were marched to the rubble of the Gorgopotamos Bridge, and gunned down by the Germans. Four days later, the Germans killed another six hostages in the same way. It wasn’t the first blood retribution for the Germans in the administration of their doctrine of collective responsibility, and it wouldn’t be the last.

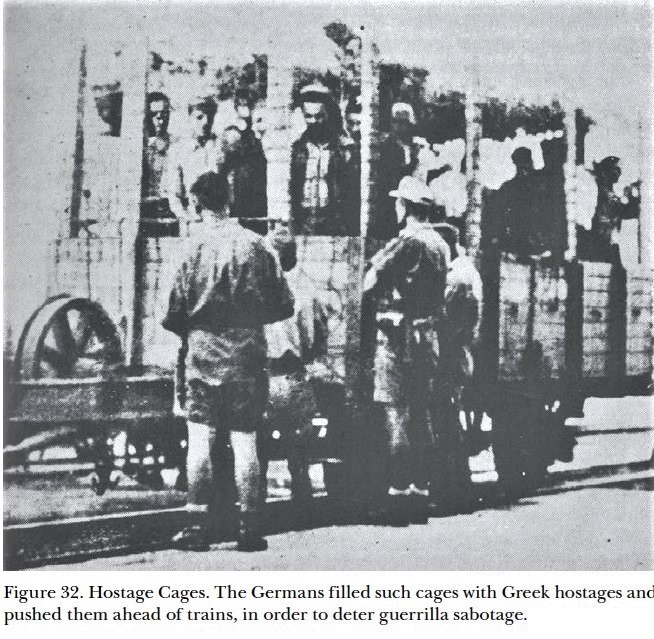

After Gorgopotamos, the Germans added klouves or crates to their trains. The Nazis filled these open railcars fenced with barbed wire with innocent Greek civilians, mostly women, and children. They coupled the cars ahead of the locomotives and shoved them first in line to discourage attack. It is impossible to overstate Nazi barbarity. Their crimes of taking hostages, and retaliatory killings, were sickening. At the Nuremberg Trials following the war, the Greek government reported 91,000 Greeks murdered as hostages and 800 villages and towns destroyed by the German occupation forces. – SJH Copyright © 2019 Steven James Hantzis

Notes

[1] http://oss-og.org/ [1] http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-WH2-2Epi-c2-WH2-2Epi-j.html page 24 [1] Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies, CASE STUDY IN GUERRILLA WAR: GREECE DURING WORLD WAR II, REVISED EDITION, United States Army Special Operations Command, page 58. [1] Myers, E.C.W. Greek Entanglement. Alan Sutton, 1985. https://books.google.com/books?id=NP1mAAAAMAAJ. Page 184. [1] Churchill’s Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare, The Mavericks Who Plotted Hitler’s Defeat – Giles Milton, page 206. [1] Churchill’s Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare, The Mavericks Who Plotted Hitler’s Defeat – Giles Milton [1] Myers, E.C.W. Greek Entanglement. Alan Sutton, 1985. https://books.google.com/books?id=NP1mAAAAMAAJ. Page 43 [1] Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies, CASE STUDY IN GUERRILLA WAR: GREECE DURING WORLD WAR II, REVISED EDITION, United States Army Special Operations Command, page 29 [1] Using Robotic Theodolites (RTS) in Structural Health Monitoring of Short-span Railway Bridges, P. Psimoulisa,b *, S. Stirosa, a Geodesy Lab., Dept. of Civil Eng., University of Patras, Patras, Greece – stiros@upatras.gr, b Geodesy and Geodynamics Lab., ETH Zurich, Schafmattstr. 34, Zurich, Switzerland – panospsimoulis@ethz.ch, page 1 https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/2011/2011_lsgi/session_1e/psimoulis_stiros.pdf [1] Myers, E.C.W. Greek Entanglement. Alan Sutton, 1985. https://books.google.com/books?id=NP1mAAAAMAAJ. Page 44 [1] Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies, CASE STUDY IN GUERRILLA WAR: GREECE DURING WORLD WAR II, REVISED EDITION, United States Army Special Operations Command, page 39 [1] Churchill’s Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare, The Mavericks Who Plotted Hitler’s Defeat – Giles Milton, page 218. [1] German Antiguerrilla Operations in the Balkans (1941-1944), CMH Publication 104-18 page 19. [1] Yada-Mc Neal, Stephan D.. Places of Shame – German and Bulgarian War Crimes in Greece 1941-1945. N.p.: Books on Demand, 2018. Page 137 [1] http://www.occupation-memories.org/en/deutsche-okkupation/Wichtige-Begriffe/index.html [1] http://www.occupation-memories.org/en/deutsche-okkupation/repressalien/index.html