Worse the First Time

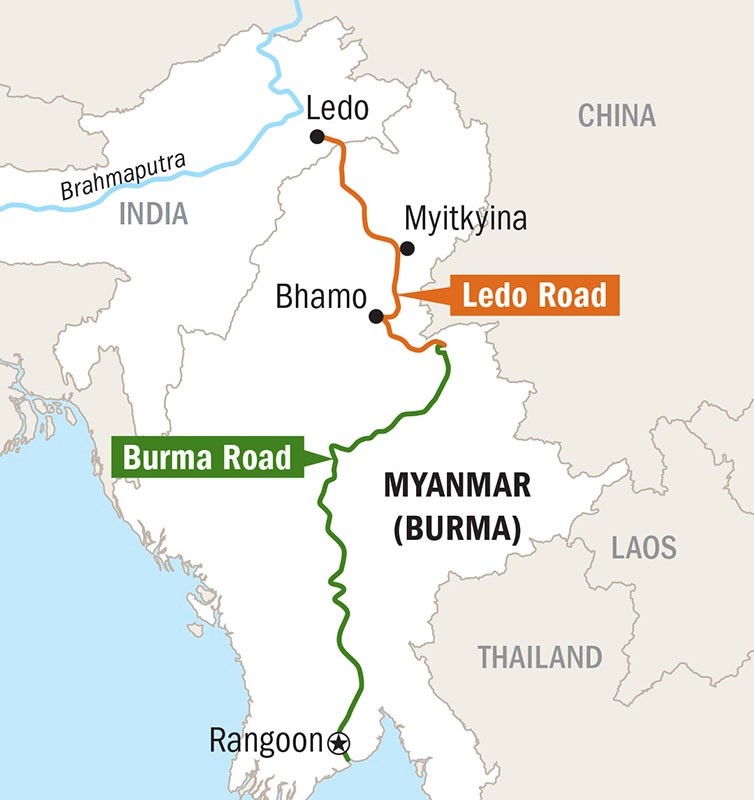

Seventy-five years ago, August 1944, Merrill’s Marauders captured Myitkyina in northern Burma eight hundred miles from where GI railroaders left them. The Marauders spent seven months in the most unforgiving jungle on earth. Their exploits are legendary. They fought thirty-two engagements including four major battles for which they were neither intended, trained, nor equipped against the entrenched, battle-hardened Japanese 18th Division. The Marauders won every time.

Then came Myitkyina. The battle lasted three months. The American victory allowed the Allies to finish the Ledo Road, secure the supply line to China, and General Slim to launch an offensive to retake Burma in December. The battle required all American hands on deck. Even men from the 721st and other railway battalions deployed to Myitkyina. Most of the 160 railroaders detailed to Burma were good men. But some volunteers were guys who were in trouble with their battalion brass; guys for whom Myitkyina was an alternative to disciplinary action. Once in Myitkyina they became the 61st Composite Group and courageously operated Jeep trains, called Bailing Wire Cannonballs, over the thirty-one miles of railroad between Myitkyina and Mogaung.

The 61st Composite Group used Jeeps for motive power because the Japanese had buried the flat rods from all but a couple of the captured locomotives. So, the resourceful GIs got busy replacing the wheels on Jeeps with rims from six-wheel-drive GMC trucks to fit the metre track gauge perfectly. Then, they chained two Jeeps together and pulled two or three flatcars loaded with troops, pipeline supplies, oil, and gas. GIs rode the flatcars to apply the handbrakes because the trusty little Jeeps had no stopping power.

To attack Myitkyina, the Marauders marched over jungle and mountain roads and paths, hacking new trails when necessary. They carried all their equipment and supplies on their backs with the help of horses and pack mules. They re-supplied by airdrops.

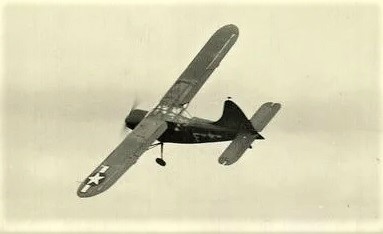

The Marauders evacuated every sick or wounded comrade. They carried casualties on makeshift stretchers of bamboo and field jackets or shirts to improvised evacuation points. These evacuation points where often remote jungle villages where the Marauders hacked out landing strips. Or, if a landing strip wasn’t at hand, they used supply drop zones, or rice paddies, or gravel bars along rivers. Brave pilots of the 71st Liaison Squadron landed and launched their sturdy Piper and Stinson evac planes in desperate conditions. The aircraft, stripped of all equipment except a compass, had room for the pilot and one stretcher — a third man onboard tempted fate.

In February 1944, 2,750 Marauders, at the peak of physical conditioning, assembled at Ledo on the Indian border and prepared to enter Burma. When they disbanded in August, they had suffered 272 killed, 955 wounded, and 980 evacuated for illness and disease. Only two of the original 2,750 survived with wounds or illness not requiring hospitalization. The following vignette is from an actual account and offered with authorial license.

My wife, Kathy, and I were honored to attend the U.S. Army’s China-Burma-India Final Round in 2005 with Rocky Agrusti, a 721st Railway Operating Battalion veteran. At our table were two Marauders who told us they had recently visited Burma. “Good grief,” I said, “You went to a country run by a military dictatorship and drug lords, with poverty and violence unrestrained? That must have been terrifying.”

The Marauder nearest me leaned in and said, “It was bad. But it was worse the first time.”

17 May 1944 – Hkumchet, State of Kachin, Burma

Corporal Harry Stevens slung his Thompson over his left shoulder and thought to himself, “Boy, I’ve seen some strange sights since I volunteered for this godforsaken outfit, but this one tops them all. God help us. This must be a first in aviation history…human catapults. If the Japs are watching, this’ll be one they’ll tell their grandchildren if I don’t kill the son-of-a-bitches first.”

A Piper L-4 Grasshopper had put down in a clearing about the size of a football field. The little airplane made the dangerous landing to evacuate a scout from I&R who had gotten badly shot up when his platoon stumbled across a Japanese machine gun nest the night before and a very ill Colonel Henry Kinnison, Jr., the unit’s commander. The clearing was soggy when the plane landed, and in the half-hour, it took to refuel and round up the wounded, a cloud burst drenched the field. Now, parked in a low spot in the clearing the plane’s main landing gear was half-submerged, and its tail-dragging third wheel was completely underwater. K Force was ready to move out, and if the Grasshopper’s passengers didn’t get help soon, they’d be goners.

Harry grabbed the side edge of the left rear wing just behind another GI. Two GIs on the other side of the airplane did the same. Four other GIs, two under each wing, pushed against the struts that ran from under the cockpit to the middle of the overhead wing.

With the pilot and the two wounded GIs aboard the rugged little plane weighed around one thousand pounds. Under normal circumstances, the L-4 would need about five hundred feet to takeoff. But nothing was normal in Burma. Harry and his buddies were there for a few more horsepower to complement the sixty-five that the Piper’s trusty air-cooled, flat-four Continental O-170 could deliver.

The GIs turned the little plane into the wind which, fortunately, was now stiff. A lanky GI in coveralls cocked the propeller and made ready to give it a spin as the pilot silently worked his checklist, “Contact, brakes, magnetos hot.”

With a thumbs-up to the GI standing in front of the plane, the pilot reached for his throttle control, and the GI gave the propeller a counter-clockwise spin. The little engine fired on the first try with a puff of blue smoke. The GI in overalls moved out of the way holding his cap on his head with his right hand. The pilot kept his feet on the brakes and advanced the throttle to the fully open position. When the RPMs hit 2,300, he released the brakes. The GIs on the rear wing ran an awkward sort of crab-shuffle and lifted the plane, raising the third wheel out of the paddy to reduce drag. The GIs in front pushed against the struts and ran as fast as they could.

They were a memorable sight with their carbines and Thompsons swinging on their shoulders and their bare asses showing through the slits they had cut in their tattered uniform trousers. Their bare asses were the sight that Harry thought the Japs might remember best.

They slit their trousers because all the GIs had dysentery and taking their pants down to relieve themselves was a waste of time and dangerous to boot. The voice of his sergeant from basic training came back to Harry now as he lifted the plane’s tail and ran sideways through the shin-deep mud tripping over the equally clumsy GI next to him, “Don’t get caught with your pants down, soldier!” Harry had heard this common chide dozens of times before volunteering for the 5307th, but it wasn’t until he started fighting in Burma that it rang true.

As the Grasshopper reached dryer ground its speed gradually outpaced that of the men’s and the GIs watched it take to the air in a sharp, steep climb out of the jungle clearing. As the little plane disappeared, Harry straightened his Thompson and stifled a humorless chuckle. – SJH